On Popular Education Page #8

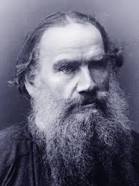

"On Popular Education" is a thought-provoking essay by Leo Tolstoy in which the renowned Russian author explores the role of education in shaping individuals and society. Written in 1862, Tolstoy critiques the existing educational systems of his time, advocating for a more accessible, practical, and moral approach to learning. He emphasizes the importance of fostering critical thinking and moral values over rote memorization, urging educators to nurture the innate curiosity of learners. Tolstoy's reflections serve as a powerful call for a more humane and equitable educational framework that empowers individuals to contribute meaningfully to society.

prone to imitate the Germans; in the second, because it was the most complicated and cunning of methods, and if it comes to taking something from abroad, of course, it has to be the latest fashion and what is most cunning; in the third, because, in particular, these methods were more than any others opposed to the old way. And thus, the new methods were taken from the Germans, and not by themselves, but with a theoretical substratum, that is, with a quasi-philosophical justification of these methods. This theoretical substratum has done great service. The moment parents or simply sensible people, who busy themselves with the question of education, express their doubt about the efficacy of these methods, they are told: "And what about Pestalozzi, and Diesterweg, and Denzel, and Wurst, and methodics, heuristics, didactics, concentrism?" and the bold people wave their hands, and say: "God be with them,--they know better." In these German methods there also lay this other advantage (the cause why they stick so eagerly to this method), that with it the teacher does not need to try too much, does not need to go on studying, does not need to work over himself and the methods of instruction. For the greater part of the time the teacher teaches by this method what the children know, and, besides, teaches it from a text-book, and that is convenient. And unconsciously, in accordance with an innate human weakness, the teacher is fond of this convenience. It is very pleasant for me, with my firm conviction that I am teaching and doing an important and very modern work, to tell the children from the book about the suslik, or about a horse's having four legs, or to transpose the cubes by twos and by threes, and ask the children how much two and two is; but if, instead of telling about the suslik, the teacher had to tell or read something interesting, to give the foundations of grammar, geography, sacred history, and of the four operations, he would at once be led to working over himself, to reading much, and to refreshing his knowledge. Thus, the old method was criticized, and a new one was taken from the Germans. This method is so foreign to our Russian un-pedantic mental attitude, its monstrosity is so glaring, that one would think that it could never have been grafted on Russia, and yet it is being applied, even though only in a small measure, and in some way gives at times better results than the old church method. This is due to the fact that, since it was taken in our country (just as it originated in Germany) from the criticism of the old method, the faults of the former method have really been rejected, though, in its extreme opposition to the old method, which, with the pedantry characteristic of the Germans, has been carried to the farthest extreme, there have appeared new faults, which are almost greater than the former ones. Formerly reading was taught in Russia by attaching to the consonants useless endings (buki--uki, vyedi--yedi), and in Germany es em de ce, and so forth, by attaching a vowel to each consonant, now in front, and now behind, and that caused some difficulty. Now they have fallen into the other extreme, by trying to pronounce the consonants without the vowels, which is an apparent impossibility. In Ushínski's grammar (Ushínski is with us the father of the sound method), and in all the manuals on sound, a consonant is defined thus: "That sound which cannot be pronounced by itself." And it is this sound which the pupil is taught before any other. When I remarked that it is impossible to pronounce b alone, but that it always gives you b[)u], I was told that was due to the inability of some persons, and that it took great skill to pronounce a consonant. And I have myself seen a teacher correct a pupil more than ten times, though he seemed quite satisfactorily to pronounce short b, until at last the pupil began to talk nonsense. And it is with these b's, that is, sounds that cannot be pronounced, as Ushínski defines them, or the pronunciation of which demands special skill, that the instruction of reading begins according to the pedantic German manuals. Formerly syllables were senselessly learned by heart (that was bad); diametrically opposed to this, the new fashion enjoins us not to divide up into syllables at all, which is absolutely impossible in a long word, and which in reality is never done. Every teacher, according to the sound method, feels the necessity of letting a pupil rest after a part of a word, having him pronounce it separately. Formerly they used to read the psalter, which, on account of its high and deep style, is incomprehensible to the children (which was bad); in contrast to this the children are made to read sentences without any contents whatever, to explain intelligible words, or to learn by heart what they cannot understand. In the old school the teacher did not speak to the pupil at all; now the teacher is ordered to talk to them on anything and everything, on what they know already, or what they do not need to know. In mathematics they formerly learned by heart the definition of operations, but now they no longer have anything to do with operations, for, according to Evtushévski, they reach numeration only in the third year, and it is assumed that for a whole year they are to be taught nothing but numbers up to ten. Formerly the pupils were made to work with large abstract numbers, without paying any attention to the other side of mathematics, to the disentanglement of the problem (the formation of an equation). Now they are taught solving puzzles, forming equations with small numbers before they know numeration and how to operate with numbers, though experience teaches any teacher that the difficulty of forming equations or the solution of puzzles are overcome by a general development in life, and not in school. It has been observed--quite correctly--that there is no greater aid for a pupil, when he is puzzled by a problem with large numbers, than to give him the same problem with smaller numbers. The pupil, who in life learns to grope through problems with small numbers, is conscious of the process of solving, and transfers this process to the problem with large numbers. Having observed this, the new pedagogues try to teach only the solving of puzzles with small numbers, that is, what cannot form the subject of instruction and is only the work of life. In the instruction of grammar the new school has again remained consistent with its point of departure,--with the criticism of the old and the adoption of the diametrically opposite method. Formerly they used to learn by heart the definition of the parts of speech, and from etymology passed over to syntax; now they not only begin with syntax, but even with logic, which the children are supposed to acquire.

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"On Popular Education Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 23 Feb. 2025. <https://www.literature.com/book/on_popular_education_3979>.

Discuss this On Popular Education book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In