On Popular Education Page #7

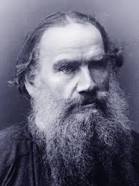

"On Popular Education" is a thought-provoking essay by Leo Tolstoy in which the renowned Russian author explores the role of education in shaping individuals and society. Written in 1862, Tolstoy critiques the existing educational systems of his time, advocating for a more accessible, practical, and moral approach to learning. He emphasizes the importance of fostering critical thinking and moral values over rote memorization, urging educators to nurture the innate curiosity of learners. Tolstoy's reflections serve as a powerful call for a more humane and equitable educational framework that empowers individuals to contribute meaningfully to society.

most comfortably stumps about in one spot. This explains why our pedagogical literature is overwhelmed with manuals for object-lessons, with manuals about how to conduct kindergartens (one of the most monstrous excrescences of the new pedagogy), with pictures and books for reading, in which are eternally repeated the same articles about the fox and the blackcock, the same poems which for some reason are written out in prose in all kinds of permutations and with all kinds of explanations; but we have not a single new article for children's reading, not one Russian, nor Church-Slavic grammar, nor a Church-Slavic dictionary, nor an arithmetic, nor a geography, nor a history for the popular schools. All the forces are absorbed in writing text-books for the instruction of children in subjects they need not and ought not to be taught in school, because they are taught them in life. Of course, there is no end to the writing of such books; for there can be only one grammar and arithmetic, but of exercises and reflections, like those I have quoted from Bunákov, and of the orders of the decomposition of numbers from Evtushévski, there may be an endless number. Pedagogy is in the same condition in which a science would be that would teach how a man ought to walk; and people would try to discover rules about how to teach the children, how to enjoin them to contract this muscle, stretch that muscle, and so forth. This condition of the new pedagogy results directly from its two fundamental principles: (1) that the aim of the school is development and not science, and (2) that development and the means for attaining it may be theoretically defined. From this has consistently resulted that miserable and frequently ridiculous condition in which the whole matter of the schools now is. Forces are wasted in vain, and the masses, who at the present moment are thirsting for education, as the dried-up grass thirsts for rain, and are ready to receive it, and beg for it,--instead of a loaf receive a stone, and are perplexed to understand whether they were mistaken in regarding education as something good, or whether something is wrong in what is being offered to them. That matters are really so there cannot be the least doubt for any man who becomes acquainted with the present theory of teaching and knows the actual condition of the school among the masses. Involuntarily there arises the question: how could honest, cultured people, who sincerely love their work and wish to do good,--for such I regard the majority of my opponents to be,--have arrived at such a strange condition and be in such deep error? This question has interested me, and I will try to communicate those answers which have occurred to me. Many causes have led to it. The most natural cause which has led pedagogy to the false path on which it now stands, is the criticism of the old order, the criticism for the sake of criticism, without positing new principles in the place of those criticized. Everybody knows that criticizing is an easy business, and that it is quite fruitless and frequently harmful, if by the side of what is condemned one does not point out the principles on the basis of which this condemnation is uttered. If I say that such and such a thing is bad because I do not like it, or because everybody says that it is bad, or even because it is really bad, but do not know how it ought to be right, the criticism will always be useless and injurious. The views of the pedagogues of the new school are, above all, based on the criticism of previous methods. Even now, when it seems there would be no sense in striking a prostrate person, we read and hear in every manual, in every discussion, "that it is injurious to read without comprehension; that it is impossible to learn by heart the definitions of numbers and operations with numbers; that senseless memorizing is injurious; that it is injurious to operate with thousands without being able to count 2-3," and so forth. The chief point of departure is the criticism of the old methods and the concoction of new ones to be as diametrically opposed to the old as possible, but by no means the positing of new foundations of pedagogy, from which new methods might result. It is very easy to criticize the old-fashioned method of studying reading by means of learning by heart whole pages of the psalter, and of studying arithmetic by memorizing what a number is, and so forth. I will remark, in the first place, that nowadays there is no need of attacking these methods, because there will hardly be found any teachers who would defend them, and, in the second place, that if, criticizing such phenomena, they want to let it be known that I am a defender of the antiquated method of instruction, it is no doubt due to the fact that my opponents, in their youth, do not know that nearly twenty years ago I with all my might and main fought against those antiquated methods of pedagogy and coöperated in their abolition. And thus it was found that the old methods of instruction were not good for anything, and, without building any new foundation, they began to look for new methods. I say "without building any new foundation," because there are only two permanent foundations of pedagogy: (1) The determination of the criterion of what ought to be taught, and (2) the criterion of how it has to be taught, that is, the determination that the chosen subjects are most necessary, and that the chosen method is the best. Nobody has even paid any attention to these foundations, and each school has in its own justification invented quasi-philosophical justificatory reflections. But this "theoretical substratum," as Mr. Bunákov has accidentally expressed himself quite well, cannot be regarded as a foundation. For the old method of instruction possessed just such a theoretical substratum. The real, peremptory question of pedagogy, which fifteen years ago I vainly tried to put in all its significance, "Why ought we to know this or that, and how shall we teach it?" has not even been touched. The result of this has been that as soon as it became apparent that the old method was not good, they did not try to find out what the best method would be, but immediately set out to discover a new method which would be the very opposite of the old one. They did as a man may do who finds his house to be cold in winter and does not trouble himself about learning why it is cold, or how to help matters, but at once tries to find another house which will as little as possible resemble the one he is living in. I was then abroad, and I remember how I everywhere came across messengers roving all over Europe in search of a new faith, that is, officials of the ministry, studying German pedagogy. We have adopted the methods of instruction current with our nearest neighbours, the Germans, in the first place, because we are always

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"On Popular Education Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 23 Feb. 2025. <https://www.literature.com/book/on_popular_education_3979>.

Discuss this On Popular Education book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In