On Popular Education Page #6

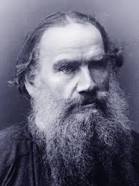

"On Popular Education" is a thought-provoking essay by Leo Tolstoy in which the renowned Russian author explores the role of education in shaping individuals and society. Written in 1862, Tolstoy critiques the existing educational systems of his time, advocating for a more accessible, practical, and moral approach to learning. He emphasizes the importance of fostering critical thinking and moral values over rote memorization, urging educators to nurture the innate curiosity of learners. Tolstoy's reflections serve as a powerful call for a more humane and equitable educational framework that empowers individuals to contribute meaningfully to society.

a collection of units as a unit of a higher order, precisely what a child does when he says: "2 and 1 = 3." He regards 2 as a kind of unit. On this law are based the consequent laws of numeration, then of addition, and of the whole of mathematics. But arbitrary conversations about the wasp, and so forth, or problems within the limit of 10,--its decomposition in every manner possible,--cannot form a subject of instruction, because, in the first place, they transcend the subject and, in the second place, because they do not treat of its laws. That is the way the matter presents itself to me from its theoretical side; but theoretical criticism may frequently err, and so I will try to verify my deductions by means of practical data. G---- P---- has given us a sample of the practical results of both object instruction and of mathematics according to Grube's method. One of the older boys was told: "Put your hand under your book!" in order to prove that he had been taught the conceptions of "over" and "under," and the intelligent boy, who, I am sure, knew what "over" and "under" was, when he was three years old, put his hand on the book when he was told to put it under it. I have all the time observed such examples, and they prove more clearly than anything else how useless, strange, and disgraceful, I feel like saying, this object instruction is for Russian children. A Russian child cannot and will not believe (he has too much respect for the teacher and for himself) that the teacher is in earnest when he asks him whether the ceiling is above or below, or how many legs he has. In arithmetic, too, we have seen that pupils who did not even know how to write the numbers and during the whole time of the instruction were exercised only in mental calculations up to 10, for half an hour did not stop blundering in every imaginable way in response to questions which the teacher put to them within the limit of 10. Evidently the instruction of mental calculation brought no results, and the syntactical difficulty, which consists in unravelling a question that is improperly put, has remained the same as ever. And thus, the practical results of the examination which took place did not confirm the usefulness of the development. But I will be more exact and conscientious. Maybe the process of development, which at first is confined not so much to the study, as to the analysis of what the pupils know already, will produce results later on. Maybe the teacher, who at first takes possession of the pupils' minds by means of the analysis, later guides them firmly and with ease, and from the narrow sphere of the descriptions of a table and the count of 2 and 1 leads them into the real sphere of knowledge, in which the pupils are no longer confined to learning what they know already, but also learn something new, and learn that new information in a new, more convenient, more intelligent manner. This supposition is confirmed by the fact that all the German pedagogues and their followers, among them Mr. Bunákov, say distinctly that object instruction is to serve as an introduction to "home science" and "natural science." But we should be looking in vain in Mr. Bunákov's manual to find out how this "home science" is to be taught, if by this word any real information is to be understood, and not the descriptions of a hut and a vestibule,--which the children know already. Mr. Bunákov, on page 200, after having explained that it is necessary to teach where the ceiling is and where the stove, says briefly: "Now it is necessary to pass over to the third stage of object instruction, the contents of which have been defined by me as follows: The study of the country, county, Government, the whole realm with its natural products and its inhabitants, in general outline, as a sketch of home science and the beginning of natural science, with the predominance of reading, which, resting on the immediate observations of the first two grades, broadens the mental horizon of the pupils,--the sphere of their concepts and ideas. We can see from the mere definition that here the objectivity appears as a complement to the explanatory reading and narrative of the teacher,--consequently, what is said in regard to the occupations of the third year has more reference to the discussion of the second occupation, which enters into the composition of the subject under instruction, which is called the native language,--the explanatory reading." We turn to the third year,--the explanatory reading, but there we find absolutely nothing to indicate how the new information is to be imparted, except that it is good to read such and such books, and in reading to put such and such questions. The questions are extremely queer (to me, at least), as, for example, the comparison of the article on water by Ushínski and of the article on water by Aksákov, and the request made of the pupils that they should explain that Aksákov considers water as a phenomenon of Nature, while Ushínski considers it as a substance, and so forth. Consequently, we find here again the same foisting of views on the pupils, and of subdivisions (generally incorrect) of the teacher, and not one word, not one hint, as to how any new knowledge is to be imparted. It is not known what shall be taught: natural history, or geography. There is nothing there but reading with questions of the character I have just mentioned. On the other side of the instruction about the word,--grammar and orthography,--we should just as much be looking in vain for any new method of instruction which is based on the preceding development. Again the old Perevlévski's grammar, which begins with philosophical definitions and then with syntactical analysis, serves as the basis of all new grammatical exercises and of Mr. Bunákov's manual. In mathematics, too, we should be looking in vain, at that stage where the real instruction in mathematics begins, for anything new and more easy, based on the whole previous instruction of the exercises of the second year up to 20. Where in arithmetic the real difficulties are met with, where it becomes necessary to explain the subject from all its sides to the pupil, as in numeration, in addition, subtraction, division, in the division and multiplication of fractions, you will not find even a shadow of anything easier, any new explanation, but only quotations from old arithmetics. The character of this instruction is everywhere one and the same. The whole attention is directed toward teaching the pupil what he already knows. And since the pupil knows what he is being taught, and easily recites in any order desired what he is asked to recite by the teacher, the teacher thinks that he is really teaching something, and the pupil's progress is great, and the teacher, paying no attention to what forms the real difficulty of teaching, that is, to teaching something new,

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"On Popular Education Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 23 Feb. 2025. <https://www.literature.com/book/on_popular_education_3979>.

Discuss this On Popular Education book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In