On Popular Education Page #9

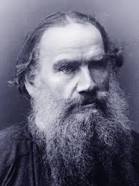

"On Popular Education" is a thought-provoking essay by Leo Tolstoy in which the renowned Russian author explores the role of education in shaping individuals and society. Written in 1862, Tolstoy critiques the existing educational systems of his time, advocating for a more accessible, practical, and moral approach to learning. He emphasizes the importance of fostering critical thinking and moral values over rote memorization, urging educators to nurture the innate curiosity of learners. Tolstoy's reflections serve as a powerful call for a more humane and equitable educational framework that empowers individuals to contribute meaningfully to society.

According to the grammar of Mr. Bunákov, which is an abbreviation of Perevlévski's grammar, even with the same choice of examples, the study of grammar begins with syntactical analysis, which is so difficult and, I will say, so uncertain for the Russian language, which does not fully comply with the classic forms of syntax. To sum up, the new school has removed certain disadvantages, of which the chief are the superfluous addition to the consonants and the memorizing of definitions, and in this it is superior to the old method, and in reading and writing sometimes gives better results; but, on the other hand, it has introduced new defects, which are that the contents of the reading are most senseless and that arithmetic is no longer taught as a study. In practice (I can refer in this to all the inspectors of schools, to all the members of school councils, who have visited the schools, and to all the teachers), in practice, in the majority of schools, where the German method is prescribed, this is what takes place, with rare exceptions. The children learn not by the sound system, but by the method of letter composition; instead of saying b, v, they say b[)u], v[)u], and break up the words into syllables. The object instruction is entirely lost sight of, arithmetic does not proceed at all, and the children have absolutely nothing to read. The teachers quite unconsciously depart from the theoretical demands and fall in with the needs of the masses. These practical results, which are repeated everywhere, should, it seems, prove the incorrectness of the method itself; but among the pedagogues, those that write manuals and prescribe rules, there exists such a complete ignorance of and aversion to the knowledge of the masses and their demands that the relation of reality to these methods does not in the least impair the progress of their business. It is hard to imagine the conception about the masses which exists in this world of the pedagogues, and from which result their method and all the consequent manner of instruction. Mr. Bunákov, in proof of how necessary the object instruction and development is for the children of a Russian school, with extraordinary naïveté adduces Pestalozzi's words: "Let any one who has lived among the common people," he says, "contradict my words that there is nothing more difficult than to impart any idea to these creatures. Nobody, indeed, gainsays that. The Swiss pastors affirm that when the people come to them to receive instruction they do not understand what they are told, and the pastors do not understand what the people say to them. City dwellers who settle in the country are amazed at the inability of the country population to express themselves; years pass before the country servants learn to express themselves to their masters." This relation of the common people in Switzerland to the cultured class is assumed as the foundation for just such a relation in Russia. I regard it as superfluous to expatiate on what is known to everybody, that in Germany the people speak a special language, called Plattdeutsch, and that in the German part of Switzerland this Plattdeutsch is especially far removed from the German language, whereas in Russia we frequently speak a bad language, while the masses always speak a good Russian, and that in Russia it will be more correct to put these words of Pestalozzi in the mouth of peasants speaking of the teachers. A peasant and his boy will say quite correctly that it is very hard to understand what those creatures, meaning the teachers, say. The ignorance about the masses is so complete in this world of the pedagogues that they boldly say that to the peasant school come little savages, and therefore boldly teach them what is down and what up, that a blackboard is placed on a stand, and that underneath it there is a groove. They do not know that if the pupils asked the teacher, there would turn up very many things which the teacher would not know; that, for example, if you rub off the paint from the board, nearly any boy will tell you of what kind of wood the board is made, whether of pine, linden, or aspen, which the teacher cannot tell; that a boy will always tell better than the teacher about a cat or a chicken, because he has observed them better than the teacher; that instead of the problem about the wagons the boy knows the problems about the crows, about the cattle, and about the geese. (About the crows: There flies a flock of crows, and there stand some oak-trees: if two crows alight on each, a crow will be lacking; if one on each, an oak-tree will be lacking. How many crows and how many oak-trees are there? About the cattle: For one hundred roubles buy one hundred animals,--calves at half a rouble, cows at three roubles, and oxen at ten roubles. How many oxen, cows, and calves are there?) The pedagogues of the German school do not even suspect that quickness of perception, that real vital development, that contempt for everything false, that ready ridicule of everything false, which are inherent in every Russian peasant boy,--and only on that account so boldly (as I myself have seen), under the fire of forty pairs of intelligent youthful eyes, perform their tricks at the risk of ridicule. For this reason, a real teacher, who knows the masses, no matter how sternly he is enjoined to teach the peasant children what is up and what down, and that two and three is five, not one real teacher, who knows the pupils with whom he has to deal, will be able to do that. Thus, the chief causes which have led us into such error are: (1) the ignorance about the masses; (2) the involuntarily seductive ease of teaching the children what they already know; (3) our proneness to imitate the Germans, and (4) the criticism of the old, without putting down a new, foundation. This last cause has led the pedagogues of the new school to this, that, in spite of the extreme external difference of the new method from the old, it is identical with it in its foundation, and, consequently, in the methods of instruction and in the results. In either method the essential principle consists in the teacher's firm and absolute knowledge of what to teach and how to teach, and this knowledge of his he does not draw from the demands of the masses and from experience, but simply decides theoretically once for all that he must teach this or that and in such a way, and so he teaches. The pedagogue of the ancient school, which for briefness' sake I shall call the church school, knows firmly and absolutely that he must teach from the prayer-book and the psalter by making the children learn by rote, and he admits no alterations in his methods; in the same manner the teacher of the new, the German, school knows firmly and absolutely that he must teach according to Bunákov and Evtushévski, begin with the words "whisker" and "wasp," ask what is up and what down, and tell about the

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"On Popular Education Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 23 Feb. 2025. <https://www.literature.com/book/on_popular_education_3979>.

Discuss this On Popular Education book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In