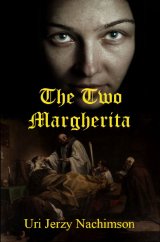

The Two Margherita: "We all have our Demons"

Contemporary Margherita meets in a church the body of Saint Margherita, who died 800 years ago; in the process of returning to the religion, she believes that happened a process of reincarnation, and the Saint's soul entered her body... This story passes through two different periods in Tuscan history, with the character of Margherita appearing at times as a holy figure of the 12th century and at times as a modern-day Margherita. Is there any connection between the two characters? Is the modern-day Margherita influenced psychologically or spiritually by the Holy Margherita? Is it a case of reincarnation? The reader will experience two historical periods, eight hundred years apart, intertwined with each other, revelations and parallel lives shrouded in mysterious, hallucinatory reality, occurring in the most beautiful region in the world, where history has always blended with romance, religion, and mystery.

Margherita D'Acquaviva was born on a cold winter day in February 1247 in a small stone house in the village of Laviano, Umbria, in the vicinity of Lake Trasimeno. It is a picturesque parish in the valley surrounded by swamps on the route from Montepulciano to the town of Cortona. The village consisted of several houses scattered throughout the valley, with a small marketplace in the center. Here, every few days, the peasants, merchants, and farmers from the nearby villages came to set up stalls to sell their wares. A small church stood among the houses, built from local white limestone found in abundance along the waterways that flowed from the hills. The entire area was inundated with swamps, as the soil was clay and couldn't absorb rainfall. As a result, the entire area became marshy and regularly flooded the surrounding villages. Overhead, on the ridge of the hill, stood a large house where the farmer Guglielmo Il Rosso, known as "Red," lived. He was given that name because of his red hair. He managed the farms of Duke Lorenzo Della Valle, who lived near Montepulciano in a castle surrounded by high walls and virtually invisible to the public. The house of Guglielmo Il Rosso was a long stone building of which a significant portion was partially used as a barn and partially used as a warehouse. In it, he stored beets and grain and also used it to hang pork forequarters for smoking. In one area, he stored tools that he distributed to farmers with whom he had a sharecropping agreement; half of the produce went to the duke, who was the landowner and the other half remained with the farmer. The house stood on the hilltop and looked down onto the valley of scattered pastures and terraces bordered with rows of small stones to protect their crops from being flooded. The stone houses in the valley below had roofs made of straw and clay that held them together. The cattle and chickens lived on the ground floor. To reach the first floor, it was necessary to climb a ladder. The floor was made of planks of rough wooden beams sawn from pine trunks and chestnut trees, trees that grow in natural woods. They grow in exposed areas suitable for farming and grazing sheep and cattle. On the floor were mattresses made of burlap stuffed with dry straw on which the family slept. The upper floor was used as the living quarters. One of those farmers was Tancredi Bartolomeo D'Acquaviva, a tall, burly hardworking man who worked all day in the field tending his grain crop, which sometimes rotted due to excess rain and sometimes was the only food the dwellers of the house ate. He lived with his wife Rosalinda, a thin woman with a pretty face, and their eight-year-old daughter Margherita, a happy girl with the face of an angel. Immediately after the birth of Margherita, Rosalinda was forced to return to work in the fields tending the cattle, so she had no choice but to have Margherita looked after by Graziella, the daughter of a neighbor. Because of her ugliness, no man wanted her, and she worked as a housekeeper to help the family put food on the table. From the day she was born, Graziella bestowed the name "Margherita" on the infant because of her beautiful shining face and golden hair. It reminded her of the white and yellow flowers scattered throughout the meadows during the spring season. Tancredi showed no interest in the naming or anything else that happened at home, but Rosalinda was very happy with the name suggested by the neighbor's girl and adopted it. When Margherita was three years old, she would stand in a field near her house and look at the sky, staring for hours, watching the clouds and the birds passing. She would do so even on rainy days, shivering in the cold and wet, staring for hours as lightning tore through the sky. Even the echoes of thunder did not frighten her. She stood there as if looking to the Creator and wondering about nature's beauty and the heavenly bodies' movement. She would flood Graziella with questions such as, "Who makes it rain?" or, "Who created the mountains, valleys, and lakes?" Graziella, being the ignoramus she was, could not answer any of her questions. Rosalinda became pregnant for the second time, and the problems began. She had contracted tuberculosis and never completely recovered from it. The pregnancy made her very weak, and she could barely get out of bed. She was constantly vomiting, and her skin became so transparent that her veins were visible. She suffered from labored breathing due to viscous mucus in her lungs. The birth was difficult because Rosalinda did not have the strength to push the baby out. The local midwife could not stop the flow of blood, which flooded the mattress while she took out the dead baby from the mother. A few hours later, she returned her soul to her maker. Rosalinda and her baby were buried next to each other in the small church graveyard where she used to pray every day. A plain wooden cross made by Tancredi marked the mound of earth under which they were buried. The father stood in front of the grave and looked at the sky as if searching for an explanation for the dual disaster that had befallen him; he was burying his wife and his newborn. He stood there for many hours waiting for some sign from heaven. When it got dark, and the snowflakes began accumulating on his hair and shoulders, he turned to go home. When he got home, he silently bowed his head while ignoring little Margherita, who was lying huddled and crying in the corner on top of a cold, damp rotting pallet. A few weeks after the death of Rosalinda, when Margherita had barely turned eight years old, her father brought home a new wife. She was short, with rude features, a dark complexion from spending much time in the Tuscan sun, and quite a bit older than Rosalinda. The relationship between her and Margherita could hardly be called loving, as the new wife did not utter a kind word to Margherita and showed no affection whatsoever. She did not care to see Margherita walking around aimlessly most of the day or sitting glued to Graziella, who gave her love and affection. Within a few months, the new wife became pregnant and ultimately gave birth to a son. Margherita was busy most of the day cultivating her vegetable garden in a small area behind the house and became completely neglected since the attention of the proud father was given entirely to the new baby. Since neither their father nor stepmother acknowledged her existence, Margherita stuck to Graziella, whom she saw as a true friend. The next year, the new wife became pregnant again and gave birth to another son. Tancredi's happiness knew no bounds as now he had two sons who eventually would be able to help him in the fields. When Margherita turned nine, Graziella left for another village, where she found steady work as a laundress at the home of a wealthy landowner. She could not earn enough money from the intermittent work that Tancredi threw her way. Margherita suffered most from Graziella's absence and began walking around barefoot and half-naked among the farm animals. During the cold winter days when she played outdoors with neighbors' children, she was not warmly dressed and was always in rags and worn-out clothes...

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"The Two Margherita: "We all have our Demons" Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 22 Feb. 2025. <https://www.literature.com/book/the_two_margherita%3A_%22we_all_have_our_demons%22_1840>.

Discuss this The Two Margherita: "We all have our Demons" book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In