The Schoolboy’s Story

"The Schoolboy’s Story" is a poignant short story by Charles Dickens that reflects on the experiences of a young schoolboy. Set in a grim educational environment, the narrative captures the child's perspective, highlighting the challenges of school life, the expectations of authority, and the longing for freedom and understanding. Through rich, evocative prose, Dickens explores themes of innocence, hardship, and the emotional struggles faced by children, ultimately serving as a critique of the education system of his time. The story conveys a sense of nostalgia and empathy for youth, urging readers to consider the impact of their own formative experiences.

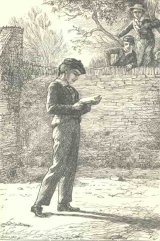

BEING rather young at present—I am getting on in years, but still I am rather young—I have no particular adventures of my own to fall back upon. It wouldn’t much interest anybody here, I suppose, to know what a screw the Reverend is, or what a griffin she is, or how they do stick it into parents—particularly hair-cutting, and medical attendance. One of our fellows was charged in his half’s account twelve and sixpence for two pills—tolerably profitable at six and threepence a-piece, I should think—and he never took them either, but put them up the sleeve of his jacket. As to the beef, it’s shameful. It’s not beef. Regular beef isn’t veins. You can chew regular beef. Besides which, there’s gravy to regular beef, and you never see a drop to ours. Another of our fellows went home ill, and heard the family doctor tell his father that he couldn’t account for his complaint unless it was the beer. Of course it was the beer, and well it might be! However, beef and Old Cheeseman are two different things. So is beer. It was Old Cheeseman I meant to tell about; not the manner in which our fellows get their constitutions destroyed for the sake of profit. Why, look at the pie-crust alone. There’s no flakiness in it. It’s solid—like damp lead. Then our fellows get nightmares, and are bolstered for calling out and waking other fellows. Who can wonder! Old Cheeseman one night walked in his sleep, put his hat on over his night-cap, got hold of a fishing-rod and a cricket-bat, and went down into the parlour, where they naturally thought from his appearance he was a Ghost. Why, he never would have done that if his meals had been wholesome. When we all begin to walk in our sleeps, I suppose they’ll be sorry for it. Old Cheeseman wasn’t second Latin Master then; he was a fellow himself. He was first brought there, very small, in a post-chaise, by a woman who was always taking snuff and shaking him—and that was the most he remembered about it. He never went home for the holidays. His accounts (he never learnt any extras) were sent to a Bank, and the Bank paid them; and he had a brown suit twice a-year, and went into boots at twelve. They were always too big for him, too. In the Midsummer holidays, some of our fellows who lived within walking distance, used to come back and climb the trees outside the playground wall, on purpose to look at Old Cheeseman reading there by himself. He was always as mild as the tea—and that’s pretty mild, I should hope!—so when they whistled to him, he looked up and nodded; and when they said, “Halloa, Old Cheeseman, what have you had for dinner?” he said, “Boiled mutton;” and when they said, “An’t it solitary, Old Cheeseman?” he said, “It is a little dull sometimes:” and then they said, “Well good-bye, Old Cheeseman!” and climbed down again. Of course it was imposing on Old Cheeseman to give him nothing but boiled mutton through a whole Vacation, but that was just like the system. When they didn’t give him boiled mutton, they gave him rice pudding, pretending it was a treat. And saved the butcher. So Old Cheeseman went on. The holidays brought him into other trouble besides the loneliness; because when the fellows began to come back, not wanting to, he was always glad to see them; which was aggravating when they were not at all glad to see him, and so he got his head knocked against walls, and that was the way his nose bled. But he was a favourite in general. Once a subscription was raised for him; and, to keep up his spirits, he was presented before the holidays with two white mice, a rabbit, a pigeon, and a beautiful puppy. Old Cheeseman cried about it—especially soon afterwards, when they all ate one another. Of course Old Cheeseman used to be called by the names of all sorts of cheeses—Double Glo’sterman, Family Cheshireman, Dutchman, North Wiltshireman, and all that. But he never minded it. And I don’t mean to say he was old in point of years—because he wasn’t—only he was called from the first, Old Cheeseman. At last, Old Cheeseman was made second Latin Master. He was brought in one morning at the beginning of a new half, and presented to the school in that capacity as “Mr. Cheeseman.” Then our fellows all agreed that Old Cheeseman was a spy, and a deserter, who had gone over to the enemy’s camp, and sold himself for gold. It was no excuse for him that he had sold himself for very little gold—two pound ten a quarter and his washing, as was reported. It was decided by a Parliament which sat about it, that Old Cheeseman’s mercenary motives could alone be taken into account, and that he had “coined our blood for drachmas.” The Parliament took the expression out of the quarrel scene between Brutus and Cassius. When it was settled in this strong way that Old Cheeseman was a tremendous traitor, who had wormed himself into our fellows’ secrets on purpose to get himself into favour by giving up everything he knew, all courageous fellows were invited to come forward and enrol themselves in a Society for making a set against him. The President of the Society was First boy, named Bob Tarter. His father was in the West Indies, and he owned, himself, that his father was worth Millions. He had great power among our fellows, and he wrote a parody, beginning— “Who made believe to be so meek That we could hardly hear him speak, Yet turned out an Informing Sneak? Old Cheeseman.” —and on in that way through more than a dozen verses, which he used to go and sing, every morning, close by the new master’s desk. He trained one of the low boys, too, a rosy-cheeked little Brass who didn’t care what he did, to go up to him with his Latin Grammar one morning, and say it so: Nominativus pronominum—Old Cheeseman, raro exprimitur—was never suspected, nisi distinctionis—of being an informer, aut emphasis gratîa—until he proved one. Ut—for instance, Vos damnastis—when he sold the boys. Quasi—as though, dicat—he should say, Pretærea nemo—I’m a Judas! All this produced a great effect on Old Cheeseman. He had never had much hair; but what he had, began to get thinner and thinner every day. He grew paler and more worn; and sometimes of an evening he was seen sitting at his desk with a precious long snuff to his candle, and his hands before his face, crying. But no member of the Society could pity him, even if he felt inclined, because the President said it was Old Cheeseman’s conscience. So Old Cheeseman went on, and didn’t he lead a miserable life! Of course the Reverend turned up his nose at him, and of course she did—because both of them always do that at all the masters—but he suffered from the fellows most, and he suffered from them constantly. He never told about it, that the Society could find out; but he got no credit for that, because the President said it was Old Cheeseman’s cowardice.

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"The Schoolboy’s Story Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 9 Mar. 2025. <https://www.literature.com/book/the_schoolboys_story_4409>.

Discuss this The Schoolboy’s Story book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In