Hunting Worse Than Slavery

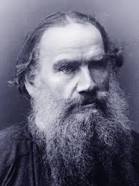

"Hunting Worse Than Slavery" is an essay by Leo Tolstoy that critiques the practice of hunting and its moral implications. In this work, Tolstoy reflects on the brutality of hunting animals for sport, arguing that it devalues life and promotes a culture of violence. He draws parallels between the suffering endured by hunted animals and the suffering experienced by enslaved people, emphasizing the need for compassion and ethical treatment of all living beings. Tolstoy's passionate advocacy for animal rights and his philosophical exploration of humanity's relationship with nature make this essay a thought-provoking read for those interested in ethics, morality, and social justice.

We were hunting bears. My companion had a chance to shoot at a bear: he wounded him, but only in a soft spot. A little blood was left on the snow, but the bear got away. We met in the forest and began to discuss what to do: whether to go and find that bear, or to wait two or three days until the bear should lie down again. We asked the peasant bear drivers whether we could now surround the bear. An old bear driver said: "No, we must give the bear a chance to calm himself. In about five days it will be possible to surround him, but if we go after him now he will only be frightened and will not lie down." But a young bear driver disputed with the old man, and said that he could surround him now. "Over this snow," he said, "the bear cannot get away far,--he is fat. He will lie down to-day again. And if he does not, I will overtake him on snow-shoes." My companion, too, did not want to surround the bear now, and advised waiting. But I said: "What is the use of discussing the matter? Do as you please, but I will go with Demyán along the track. If we overtake him, so much is gained; if not,--I have nothing else to do to-day anyway, and it is not yet late." And so we did. My companions went to the sleigh, and back to the village, but Demyán and I took bread with us, and remained in the woods. When all had left us, Demyán and I examined our guns, tucked our fur coats over our belts, and followed the track. It was fine weather, chilly and calm. But walking on snow-shoes was a hard matter: the snow was deep and powdery. The snow had not settled in the forest, and, besides, fresh snow had fallen on the day before, so that the snow-shoes sunk half a foot in the snow, and in places even deeper. The bear track could be seen a distance away. We could see the way the bear had walked, for in spots he had fallen in the snow to his belly and had swept the snow aside. At first we walked in plain sight of the track, through a forest of large trees; then, when the track went into a small pine wood, Demyán stopped. "We must now give up the track," he said. "He will, no doubt, lie down here. He has been sitting on his haunches,--you can see it by the snow. Let us go away from the track, and make a circle around him. But we must walk softly and make no noise, not even cough, or we shall scare him." We went away from the track, to the left. We walked about five hundred steps and there we again saw the track before us. We again followed the track, and this took us to the road. We stopped on the road and began to look around, to see in what direction the bear had gone. Here and there on the road we could see the bear's paws with all the toes printed on the snow, while in others we could see the tracks of a peasant's bast shoes. He had, evidently, gone to the village. We walked along the road. Demyán said to me: "We need not watch the road; somewhere he will turn off the road, to the right or to the left,--we shall see in the snow. Somewhere he will turn off,--he will not go to the village." We walked thus about a mile along the road; suddenly we saw the track turn off from the road. We looked at it, and see the wonder! It was a bear's track, but leading not from the road to the woods, but from the woods to the road: the toes were turned to the road. I said: "That is another bear." Demyán looked at it, and thought awhile. "No," he said, "that is the same bear, only he has begun to cheat. He left the road backwards." We followed the track, and so it was. The bear had evidently walked about ten steps backwards from the road, until he got beyond a fir-tree, and then he had turned and gone on straight ahead. Demyán stopped, and said: "Now we shall certainly fall in with him. He has no place but this swamp to lie down in. Let us surround him." We started to surround him, going through the dense pine forest. I was getting tired, and it was now much harder to travel. Now I would strike against a juniper-bush, and get caught in it; or a small pine-tree would get under my feet; or the snow-shoes would twist, as I was not used to them; or I would strike a stump or a block under the snow. I was beginning to be worn out. I took off my fur coat, and the sweat was just pouring down from me. But Demyán sailed along as in a boat. It looked as though the snow-shoes walked under him of their own accord. He neither caught in anything, nor did his shoes turn on him. And he even threw my fur coat over his shoulders, and kept urging me on. We made about three versts in a circle, and walked past the swamp. Demyán suddenly stopped in front of me, and waved his hand. I walked over to him. Demyán bent down, and pointed with his hand, and whispered to me: "Do you see, a magpie is chattering on a windfall: the bird is scenting the bear from a distance. It is he." We walked to one side, made another verst, and again hit the old trail. Thus we had made a circle around the bear, and he was inside of it. We stopped. I took off my hat and loosened my wraps: I felt as hot as in a bath, and was as wet as a mouse. Demyán, too, was all red, and he wiped his face with his sleeve. "Well," he said, "we have done our work, sir, so we may take a rest." The evening glow could be seen through the forest. We sat down on the snow-shoes to rest ourselves. We took the bread and salt out of the bags; first I ate a little snow, and then the bread. The bread tasted to me better than any I had eaten in all my life. We sat awhile; it began to grow dark. I asked Demyán how far it was to the village. "About twelve versts. We shall reach it in the night; but now we must rest. Put on your fur coat, sir, or you will catch a cold." Demyán broke off some pine branches, knocked down the snow, made a bed, and we lay down beside each other, with our arms under our heads. I do not remember how I fell asleep. I awoke about two hours later. Something crashed. I had been sleeping so soundly that I forgot where I was. I looked around me: what marvel was that? Where was I? Above me were some white chambers, and white posts, and on everything glistened white tinsel. I looked up: there was a white, checkered cloth, and between the checks was a black vault in which burned fires of all colours. I looked around, and I recalled that we were in the forest, and that the snow-covered trees had appeared to me as chambers, and that the fires were nothing but the stars that flickered between the branches. In the night a hoarfrost had fallen, and there was hoarfrost on the branches, and on my fur coat, and Demyán was all covered with hoarfrost, and hoarfrost fell from above. I awoke Demyán. We got up on our snow-shoes and started. The forest was quiet. All that could be heard was the sound we made as we slid on our snow-shoes over the soft snow, or when a tree would crackle from the frost, and a hollow sound would

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Hunting Worse Than Slavery Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 22 Feb. 2025. <https://www.literature.com/book/hunting_worse_than_slavery_3957>.

Discuss this Hunting Worse Than Slavery book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In