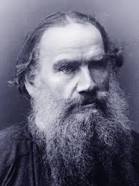

A Prisoner of the Caucasus

"A Prisoner of the Caucasus" is a novella by Leo Tolstoy that explores themes of captivity, humanity, and the harsh realities of war. Set in the Caucasus mountains during the 19th century, the story follows a Russian soldier who is taken prisoner by Chechen rebels. As he grapples with the danger and uncertainty of his situation, he reflects on his own values, the nature of freedom, and the complex relationships between captor and captive. Through vivid descriptions and poignant insights, Tolstoy delves into the psychological and moral dilemmas encountered during conflict, showcasing his profound understanding of human nature.

I. A certain gentleman was serving as an officer in the Caucasus. His name was Zhilín. One day he received a letter from home. His old mother wrote to him: "I have grown old, and I should like to see my darling son before my death. Come to bid me farewell and bury me, and then, with God's aid, return to the service. I have also found a bride for you: she is bright and pretty and has property. If you take a liking to her, you can marry her, and stay here for good." Zhilín reflected: "Indeed, my old mother has grown feeble; perhaps I shall never see her again. I must go; and if the bride is a good girl, I may marry her." He went to the colonel, got a furlough, bade his companions good-bye, treated his soldiers to four buckets of vódka, and got himself ready to go. At that time there was a war in the Caucasus. Neither in the daytime, nor at night, was it safe to travel on the roads. The moment a Russian walked or drove away from a fortress, the Tartars either killed him or took him as a prisoner to the mountains. It was a rule that a guard of soldiers should go twice a week from fortress to fortress. In front and in the rear walked soldiers, and between them were other people. It was in the summer. The carts gathered at daybreak outside the fortress, and the soldiers of the convoy came out, and all started. Zhilín rode on horseback, and his cart with his things went with the caravan. They had to travel twenty-five versts. The caravan proceeded slowly; now the soldiers stopped, and now a wheel came off a cart, or a horse stopped, and all had to stand still and wait. The sun had already passed midday, but the caravan had made only half the distance. It was dusty and hot; the sun just roasted them, and there was no shelter: it was a barren plain, with neither tree nor bush along the road. Zhilín rode out ahead. He stopped and waited for the caravan to catch up with him. He heard them blow the signal-horn behind: they had stopped again. Zhilín thought: "Why can't I ride on, without the soldiers? I have a good horse under me, and if I run against Tartars, I will gallop away. Or had I better not go?" He stopped to think it over. There rode up to him another officer, Kostylín, with a gun, and said: "Let us ride by ourselves, Zhilín! I cannot stand it any longer: I am hungry, and it is so hot. My shirt is dripping wet." Kostylín was a heavy, stout man, with a red face, and the perspiration was just rolling down his face. Zhilín thought awhile and said: "Is your gun loaded?" "It is." "Well, then, we will go, but on one condition, that we do not separate." And so they rode ahead on the highway. They rode through the steppe, and talked, and looked about them. They could see a long way off. When the steppe came to an end, the road entered a cleft between two mountains. So Zhilín said: "We ought to ride up the mountain to take a look; for here they may leap out on us from the mountain without our seeing them." But Kostylín said: "What is the use of looking? Let us ride on!" Zhilín paid no attention to him. "No," he said, "you wait here below, and I will take a look up there." And he turned his horse to the left, up-hill. The horse under Zhilín was a thoroughbred (he had paid a hundred roubles for it when it was a colt, and had himself trained it), and it carried him up the slope as though on wings. The moment he reached the summit, he saw before him a number of Tartars on horseback, about eighty fathoms away. There were about thirty of them. When he saw them, he began to turn back; and the Tartars saw him, and galloped toward him, and on the ride took their guns out of the covers. Zhilín urged his horse down-hill as fast as its legs would carry him, and he shouted to Kostylín: "Take out the gun!" and he himself thought about his horse: "Darling, take me away from here! Don't stumble! If you do, I am lost. If I get to the gun, they shall not catch me." But Kostylín, instead of waiting, galloped at full speed toward the fortress, the moment he saw the Tartars. He urged the horse on with the whip, now on one side, and now on the other. One could see through the dust only the horse switching her tail. Zhilín saw that things were bad. The gun had disappeared, and he could do nothing with a sword. He turned his horse back to the soldiers, thinking that he might get away. He saw six men crossing his path. He had a good horse under him, but theirs were better still, and they crossed his path. He began to check his horse: he wanted to turn around; but the horse was running at full speed and could not be stopped, and he flew straight toward them. He saw a red-bearded Tartar on a gray horse, who was coming near to him. He howled and showed his teeth, and his gun was against his shoulder. "Well," thought Zhilín, "I know you devils. When you take one alive, you put him in a hole and beat him with a whip. I will not fall into your hands alive----" Though Zhilín was not tall, he was brave. He drew his sword, turned his horse straight against the Tartar, and thought: "Either I will knock his horse off its feet, or I will strike the Tartar with my sword." Zhilín got within a horse's length from him, when they shot at him from behind and hit the horse. The horse dropped on the ground while going at full speed, and fell on Zhilín's leg. He wanted to get up, but two stinking Tartars were already astride of him. He tugged and knocked down the two Tartars, but three more jumped down from their horses and began to strike him with the butts of their guns. Things grew dim before his eyes, and he tottered. The Tartars took hold of him, took from their saddles some reserve straps, twisted his arms behind his back, tied them with a Tartar knot, and fastened him to the saddle. They knocked down his hat, pulled off his boots, rummaged all over him, and took away his money and his watch, and tore all his clothes. Zhilín looked back at his horse. The dear animal was lying just as it had fallen down, and only twitched its legs and did not reach the ground with them; in its head there was a hole, and from it the black blood gushed and wet the dust for an ell around. A Tartar went up to the horse, to pull off the saddle. The horse was struggling still, and so he took out his dagger and cut its throat. A whistling sound came from the throat, and the horse twitched, and was dead. The Tartars took off the saddle and the trappings. The red-bearded Tartar mounted his horse, and the others seated Zhilín behind him. To prevent his falling off, they attached him by a strap to the Tartar's belt, and they rode off to the mountains. Zhilín was sitting back of the Tartar, and shaking and striking with his face against the stinking Tartar's back. All he saw before him was the mighty back, and the muscular neck, and the livid, shaved nape of his

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"A Prisoner of the Caucasus Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 22 Feb. 2025. <https://www.literature.com/book/a_prisoner_of_the_caucasus_3958>.

Discuss this A Prisoner of the Caucasus book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In