The Two Old Men Page #2

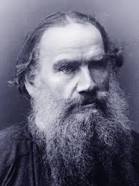

"The Two Old Men" is a short moral tale by Leo Tolstoy that explores themes of friendship, generosity, and the human capacity for kindness. The story revolves around two elderly men who, despite their different approaches to life, embark on a journey together. As they encounter various challenges and situations, they reflect on their past decisions and life lessons. Ultimately, the narrative highlights the importance of compassion and understanding in nurturing meaningful relationships and the value of selflessness in human interactions. Through its simple yet profound storytelling, Tolstoy invites readers to contemplate their own values and behaviors in the context of friendship and community.

stepped away from his companion so as not to lead him into sin, and took a pinch. Efím Tarásych walked firmly and well; he did no wrong and spoke no vain words, but there was no lightness in his heart. The cares about his home did not leave his mind. He was thinking all the time about what was going on at home,--whether he had not forgotten to give his son some order, and whether his son was doing things in the right way. When he saw along the road that they were setting out potatoes or hauling manure, he wondered whether his son was doing as he had been ordered. He just felt like returning, and showing him what to do, and doing it himself. III. The old men walked for live weeks. They wore out their home-made bast shoes and began to buy new ones. They reached the country of the Little-Russians. Heretofore they had been paying for their night's lodging and for their dinner, but when they came to the Little-Russians, people vied with each other in inviting them to their houses. They let them come in, and fed them, and took no money from them, but even filled their wallets with bread, and now and then with flat cakes. Thus the old men walked without expense some seven hundred versts. They crossed another Government and came to a place where there had been a failure of crops. There they let them into the houses and did not take any money for their night's lodging, but would not feed them. And they did not give them bread everywhere,--not even for money could the old men get any in some places. The previous year, so the people said, nothing had grown. Those who had been rich were ruined,--they sold everything; those who had lived in comfort came down to nothing; and the poor people either entirely left the country, or turned beggars, or just managed to exist at home. In the winter they lived on chaff and orach. One night the two old men stayed in a borough. There they bought about fifteen pounds of bread. In the morning they left before daybreak, so that they might walk a good distance before the heat. They marched some ten versts and reached a brook. They sat down, filled their cups with water, softened the bread with it and ate it, and changed their leg-rags. They sat awhile and rested themselves. Eliséy took out his snuff-horn. Efím Tarásych shook his head at him. "Why don't you throw away that nasty thing?" he asked. Eliséy waved his hand. "Sin has overpowered me," he said. "What shall I do?" They got up and marched on. They walked another ten versts. They came to a large village, and passed through it. It was quite warm then. Eliséy was tired, and wanted to stop and get a drink, but Tarásych would not stop. Tarásych was a better walker, and Eliséy had a hard time keeping up with him. "I should like to get a drink," he said. "Well, drink! I do not want any." Eliséy stopped. "Do not wait for me," he said. "I will just run into a hut and get a drink of water. I will catch up with you at once." "All right," he said. And Efím Tarásych proceeded by himself along the road, while Eliséy turned to go into a hut. Eliséy came up to the hut. It was a small clay cabin; the lower part was black, the upper white, and the clay had long ago crumbled off,--evidently it had not been plastered for a long time,--and the roof was open at one end. The entrance was from the yard. Eliséy stepped into the yard, and there saw that a lean, beardless man with his shirt stuck in his trousers in Little-Russian fashion was lying near the earth mound. The man had evidently lain down in a cool spot, but now the sun was burning down upon him. He was lying there awake. Eliséy called out to him, asking him to give him a drink, but the man made no reply. "He is either sick, or an unkind man," thought Eliséy, going up to the door. Inside he heard a child crying. He knocked with the door-ring. "Good people!" No answer. He struck with his staff against the door. "Christian people!" No stir. "Servants of the Lord!" No reply. Eliséy was on the point of going away, when he heard somebody groaning within. "I wonder whether some misfortune has happened there to the people. I must see." And Eliséy went into the hut. IV. Eliséy turned the ring,--the door was not locked. He pushed the door open and walked through the vestibule. The door into the living-room was open. On the left there was an oven; straight ahead was the front corner; in the corner stood a shrine and a table; beyond the table was a bench, and on it sat a bareheaded old woman, in nothing but a shirt; her head was leaning on the table, and near her stood a lean little boy, his face as yellow as wax and his belly swollen, and he was pulling the old woman's sleeve, and crying at the top of his voice and begging for something. Eliséy entered the room. There was a stifling air in the house. He saw a woman lying behind the oven, on the floor. She was lying on her face without looking at anything, and snoring, and now stretching out a leg and again drawing it up. And she tossed from side to side,--and from her came that oppressive smell: evidently she was very sick, and there was nobody to take her away. The old woman raised her head, when she saw the man. "What do you want?" she said, in Little-Russian. "What do you want? We have nothing, my dear man." Eliséy understood what she was saying: he walked over to her. "Servant of the Lord," he said, "I have come in to get a drink of water." "There is none, I say, there is none. There is nothing here for you to take. Go!" Eliséy asked her: "Is there no well man here to take this woman away?" "There is nobody here: the man is dying in the yard, and we here." The boy grew quiet when he saw the stranger, but when the old woman began to speak, he again took hold of her sleeve. "Bread, granny, bread!" and he burst out weeping. Just as Eliséy was going to ask the old woman another question, the man tumbled into the hut; he walked along the wall and wanted to sit down on the bench, but before reaching it he fell down in the corner, near the threshold. He did not try to get up, but began to speak. He would say one word at a time, then draw his breath, then say something again. "We are sick," he said, "and--hungry. The boy is starving." He indicated the boy with his head and began to weep. Eliséy shifted his wallet on his back, freed his arms, let the wallet down on the ground, lifted it on the bench, and untied it. When it was open, he took out the bread and the knife, out off a slice, and gave it to the man. The man did not take it, but pointed to the boy and the girl, to have it given to them. Eliséy gave it to the boy. When the boy saw the bread, he made for it, grabbed the slice with both his hands, and stuck his nose into the bread. A girl crawled out from behind the oven and gazed at the bread. Eliséy gave her, too, a piece. He cut off

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"The Two Old Men Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 22 Feb. 2025. <https://www.literature.com/book/the_two_old_men_3983>.

Discuss this The Two Old Men book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In