The Test Page #2

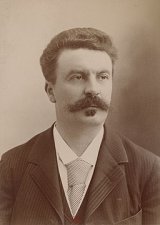

"The Test" by Guy de Maupassant is a compelling short story that explores themes of love, fidelity, and the complexities of human relationships. The narrative revolves around a man's emotional turmoil as he grapples with jealousy and mistrust after he suspects his wife of infidelity. To confirm his doubts, he devises a test to gauge her loyalty, leading to unexpected revelations about both their characters and the nature of trust. Maupassant masterfully captures the intricacies of the human psyche and the consequences of insecurity, ultimately prompting readers to reflect on the fragility of love and the dangerous repercussions of unchecked suspicion.

Bondel immediately thought: “There is no doubt; my wife was right!” When he left this man he began to think things over again. He felt in his soul a strange confusion of contradictory ideas, a sort of interior burning; that mocking, impertinent laugh kept ringing in his ears and seemed to say: “Why; you are just the same as the others, you fool!” That was indeed bravado, one of those pieces of impudence of which a woman makes use when she dares everything, risks everything, to wound and humiliate the man who has aroused her ire. This poor man must also be one of those deceived husbands, like so many others. He had said sadly: “There are times when she seems to have more confidence and faith in our friends than in me.” That is how a husband formulated his observations on the particular attentions of his wife for another man. That was all. He had seen nothing more. He was like the rest—all the rest! And how strangely Bondel's own wife had laughed as she said: “You, too —you, too.” How wild and imprudent these creatures are who can arouse such suspicions in the heart for the sole purpose of revenge! He ran over their whole life since their marriage, reviewed his mental list of their acquaintances, to see whether she had ever appeared to show more confidence in any one else than in himself. He never had suspected any one, he was so calm, so sure of her, so confident. But, now he thought of it, she had had a friend, an intimate friend, who for almost a year had dined with them three times a week. Tancret, good old Tancret, whom he, Bendel, loved as a brother and whom he continued to see on the sly, since his wife, he did not know why, had grown angry at the charming fellow. He stopped to think, looking over the past with anxious eyes. Then he grew angry at himself for harboring this shameful insinuation of the defiant, jealous, bad ego which lives in all of us. He blamed and accused himself when he remembered the visits and the demeanor of this friend whom his wife had dismissed for no apparent reason. But, suddenly, other memories returned to him, similar ruptures due to the vindictive character of Madame Bondel, who never pardoned a slight. Then he laughed frankly at himself for the doubts which he had nursed; and he remembered the angry looks of his wife as he would tell her, when he returned at night: “I saw good old Tancret, and he wished to be remembered to you,” and he reassured himself. She would invariably answer: “When you see that gentleman you can tell him that I can very well dispense with his remembrances.” With what an irritated, angry look she would say these words! How well one could feel that she did not and would not forgive—and he had suspected her even for a second? Such foolishness! But why did she grow so angry? She never had given the exact reason for this quarrel. She still bore him that grudge! Was it?—But no—no—and Bondel declared that he was lowering himself by even thinking of such things. Yes, he was undoubtedly lowering himself, but he could not help thinking of it, and he asked himself with terror if this thought which had entered into his mind had not come to stop, if he did not carry in his heart the seed of fearful torment. He knew himself; he was a man to think over his doubts, as formerly he would ruminate over his commercial operations, for days and nights, endlessly weighing the pros and the cons. He was already becoming excited; he was walking fast and losing his calmness. A thought cannot be downed. It is intangible, cannot be caught, cannot be killed. Suddenly a plan occurred to him; it was bold, so bold that at first he doubted whether he would carry it out. Each time that he met Tancret, his friend would ask for news of Madame Bondel, and Bondel would answer: “She is still a little angry.” Nothing more. Good Lord! What a fool he had been! Perhaps! Well, he would take the train to Paris, go to Tancret, and bring him back with him that very evening, assuring him that his wife's mysterious anger had disappeared. But how would Madame Bondel act? What a scene there would be! What anger! what scandal! What of it?—that would be revenge! When she should come face to face with him, unexpectedly, he certainly ought to be able to read the truth in their expressions. He immediately went to the station, bought his ticket, got into the car, and as soon as he felt him self being carried away by the train, he felt a fear, a kind of dizziness, at what he was going to do. In order not to weaken, back down, and return alone, he tried not to think of the matter any longer, to bring his mind to bear on other affairs, to do what he had decided to do with a blind resolution; and he began to hum tunes from operettas and music halls until he reached Paris. As soon as he found himself walking along the streets that led to Tancret's, he felt like stopping, He paused in front of several shops, noticed the prices of certain objects, was interested in new things, felt like taking a glass of beer, which was not his usual custom; and as he approached his friend's dwelling he ardently hoped not meet him. But Tancret was at home, alone, reading. He jumped up in surprise, crying: “Ah! Bondel! what luck!” Bondel, embarrassed, answered: “Yes, my dear fellow, I happened to be in Paris, and I thought I'd drop in and shake hands with you.” “That's very nice, very nice! The more so that for some time you have not favored me with your presence very often.” “Well, you see—even against one's will, one is often influenced by surrounding conditions, and as my wife seemed to bear you some ill-will—” “Jove! 'seemed'—she did better than that, since she showed me the door.” “What was the reason? I never heard it.” “Oh! nothing at all—a bit of foolishness—a discussion in which we did not both agree.” “But what was the subject of this discussion?” “A lady of my acquaintance, whom you may perhaps know by name, Madame Boutin.” “Ah! really. Well, I think that my wife has forgotten her grudge, for this very morning she spoke to me of you in very pleasant terms.” Tancret started and seemed so dumfounded that for a few minutes he could find nothing to say. Then he asked: “She spoke of me—in pleasant terms?” “Yes.” “You are sure?” “Of course I am. I am not dreaming.” “And then?” “And then—as I was coming to Paris I thought that I would please you by coming to tell you the good news.” “Why, yes—why, yes—” Bondel appeared to hesitate; then, after a short pause, he added: “I even had an idea.” “What is it?” “To take you back home with me to dinner.” Tancret, who was naturally prudent, seemed a little worried by this proposition, and he asked: “Oh! really—is it possible? Are we not exposing ourselves to—to—a scene?” “No, no, indeed!” “Because, you know, Madame Bendel bears malice for a long time.” “Yes, but I can assure you that she no longer bears you any ill—will. I am even convinced that it will be a great pleasure for her to see you thus, unexpectedly.”

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"The Test Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 9 Mar. 2025. <https://www.literature.com/book/the_test_4085>.

Discuss this The Test book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In