The Iron Heel Page #8

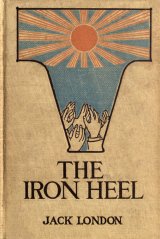

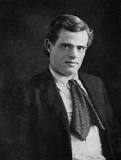

"The Iron Heel" by Jack London, published in 1908, is a dystopian political novel that explores themes of authoritarianism, class struggle, and revolution. It is considered one of the earliest examples of dystopian fiction, influencing later works like 1984 and Brave New World.

[3] In those days, groups of predatory individuals controlled all the means of transportation, and for the use of same levied toll upon the public. “Very good,” the Bishop interposed. “And there is no reason that the division should not be amicable.” “You have already forgotten what we had agreed upon,” Ernest replied. “We agreed that the average man is selfish. He is the man that is. You have gone up in the air and are arranging a division between the kind of men that ought to be but are not. But to return to the earth, the workingman, being selfish, wants all he can get in the division. The capitalist, being selfish, wants all he can get in the division. When there is only so much of the same thing, and when two men want all they can get of the same thing, there is a conflict of interest between labor and capital. And it is an irreconcilable conflict. As long as workingmen and capitalists exist, they will continue to quarrel over the division. If you were in San Francisco this afternoon, you’d have to walk. There isn’t a street car running.” “Another strike?”[4] the Bishop queried with alarm. [4] These quarrels were very common in those irrational and anarchic times. Sometimes the laborers refused to work. Sometimes the capitalists refused to let the laborers work. In the violence and turbulence of such disagreements much property was destroyed and many lives lost. All this is inconceivable to us—as inconceivable as another custom of that time, namely, the habit the men of the lower classes had of breaking the furniture when they quarrelled with their wives. “Yes, they’re quarrelling over the division of the earnings of the street railways.” Bishop Morehouse became excited. “It is wrong!” he cried. “It is so short-sighted on the part of the workingmen. How can they hope to keep our sympathy—” “When we are compelled to walk,” Ernest said slyly. But Bishop Morehouse ignored him and went on: “Their outlook is too narrow. Men should be men, not brutes. There will be violence and murder now, and sorrowing widows and orphans. Capital and labor should be friends. They should work hand in hand and to their mutual benefit.” “Ah, now you are up in the air again,” Ernest remarked dryly. “Come back to earth. Remember, we agreed that the average man is selfish.” “But he ought not to be!” the Bishop cried. “And there I agree with you,” was Ernest’s rejoinder. “He ought not to be selfish, but he will continue to be selfish as long as he lives in a social system that is based on pig-ethics.” The Bishop was aghast, and my father chuckled. “Yes, pig-ethics,” Ernest went on remorselessly. “That is the meaning of the capitalist system. And that is what your church is standing for, what you are preaching for every time you get up in the pulpit. Pig-ethics! There is no other name for it.” Bishop Morehouse turned appealingly to my father, but he laughed and nodded his head. “I’m afraid Mr. Everhard is right,” he said. “Laissez-faire, the let-alone policy of each for himself and devil take the hindmost. As Mr. Everhard said the other night, the function you churchmen perform is to maintain the established order of society, and society is established on that foundation.” “But that is not the teaching of Christ!” cried the Bishop. “The Church is not teaching Christ these days,” Ernest put in quickly. “That is why the workingmen will have nothing to do with the Church. The Church condones the frightful brutality and savagery with which the capitalist class treats the working class.” “The Church does not condone it,” the Bishop objected. “The Church does not protest against it,” Ernest replied. “And in so far as the Church does not protest, it condones, for remember the Church is supported by the capitalist class.” “I had not looked at it in that light,” the Bishop said naively. “You must be wrong. I know that there is much that is sad and wicked in this world. I know that the Church has lost the—what you call the proletariat.”[5] [5] Proletariat: Derived originally from the Latin proletarii, the name given in the census of Servius Tullius to those who were of value to the state only as the rearers of offspring (proles); in other words, they were of no importance either for wealth, or position, or exceptional ability. “You never had the proletariat,” Ernest cried. “The proletariat has grown up outside the Church and without the Church.” “I do not follow you,” the Bishop said faintly. “Then let me explain. With the introduction of machinery and the factory system in the latter part of the eighteenth century, the great mass of the working people was separated from the land. The old system of labor was broken down. The working people were driven from their villages and herded in factory towns. The mothers and children were put to work at the new machines. Family life ceased. The conditions were frightful. It is a tale of blood.” “I know, I know,” Bishop Morehouse interrupted with an agonized expression on his face. “It was terrible. But it occurred a century and a half ago.” “And there, a century and a half ago, originated the modern proletariat,” Ernest continued. “And the Church ignored it. While a slaughter-house was made of the nation by the capitalist, the Church was dumb. It did not protest, as to-day it does not protest. As Austin Lewis[6] says, speaking of that time, those to whom the command ‘Feed my lambs’ had been given, saw those lambs sold into slavery and worked to death without a protest.[7] The Church was dumb, then, and before I go on I want you either flatly to agree with me or flatly to disagree with me. Was the Church dumb then?” [6] Candidate for Governor of California on the Socialist ticket in the fall election of 1906 Christian Era. An Englishman by birth, a writer of many books on political economy and philosophy, and one of the Socialist leaders of the times. [7] There is no more horrible page in history than the treatment of the child and women slaves in the English factories in the latter half of the eighteenth century of the Christian Era. In such industrial hells arose some of the proudest fortunes of that day. Bishop Morehouse hesitated. Like Dr. Hammerfield, he was unused to this fierce “infighting,” as Ernest called it. “The history of the eighteenth century is written,” Ernest prompted. “If the Church was not dumb, it will be found not dumb in the books.” “I am afraid the Church was dumb,” the Bishop confessed. “And the Church is dumb to-day.” “There I disagree,” said the Bishop. Ernest paused, looked at him searchingly, and accepted the challenge. “All right,” he said. “Let us see. In Chicago there are women who toil all the week for ninety cents. Has the Church protested?” “This is news to me,” was the answer. “Ninety cents per week! It is

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"The Iron Heel Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 10 Mar. 2025. <https://www.literature.com/book/the_iron_heel_4275>.

Discuss this The Iron Heel book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In