The Candle Page #2

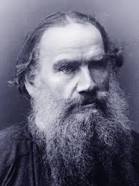

"The Candle" is a short story by Leo Tolstoy that explores themes of morality, faith, and the fleeting nature of life. The narrative centers around a candle that symbolizes the human soul and the transient nature of existence. In a poignant and introspective style, Tolstoy reflects on how individuals often squander their time and fail to recognize the importance of living purposefully. Through the tale, he invites readers to contemplate the deeper meaning of their actions and the significance of every moment in the light of their mortality. The story serves as a reminder to cherish life and make choices that reflect one's true values.

indignation meeting. “If he has really forgotten God,” they said, “and shall continue to commit such crimes against us, it is truly necessary that we should kill him. If not, let us perish, for it can make no difference to us now.” This despairing programme, however, met with considerable opposition from a peaceably-inclined man named Peter Mikhayeff. “Brethren,” said he, “you are contemplating a grievous sin. The taking of human life is a very serious matter. Of course it is easy to end the mortal existence of a man, but what will become of the souls of those who commit the deed? If Michael continues to act toward us unjustly God will surely punish him. But, my friends, we must have patience.” This pacific utterance only served to intensify the anger of Vasili. Said he: “Peter is forever repeating the same old story, ‘It is a sin to kill any one.’ Certainly it is sinful to murder; but we should consider the kind of man we are dealing with. We all know it is wrong to kill a good man, but even God would take away the life of such a dog as he is. It is our duty, if we have any love for mankind, to shoot a dog that is mad. It is a sin to let him live. If, therefore, we are to suffer at all, let it be in the interests of the people—and they will thank us for it. If we remain quiet any longer a flogging will be our only reward. You are talking nonsense, Mikhayeff. Why don’t you think of the sin we shall be committing if we work during the Easter holidays—for you will refuse to work then yourself?” “Well, then,” replied Peter, “if they shall send me to plough, I will go. But I shall not be going of my own free will, and God will know whose sin it is, and shall punish the offender accordingly. Yet we must not forget him. Brethren, I am not giving you my own views only. The law of God is not to return evil for evil; indeed, if you try in this way to stamp out wickedness it will come upon you all the stronger. It is not difficult for you to kill the man, but his blood will surely stain your own soul. You may think you have killed a bad man—that you have gotten rid of evil—but you will soon find out that the seeds of still greater wickedness have been planted within you. If you yield to misfortune it will surely come to you.” As Peter was not without sympathizers among the peasants, the poor serfs were consequently divided into two groups: the followers of Vasili and those who held the views of Mikhayeff. On Easter Sunday no work was done. Toward the evening an elder came to the peasants from the nobleman’s court and said: “Our superintendent, Michael Simeonovitch, orders you to go to-morrow to plough the field for the oats.” Thus the official went through the village and directed the men to prepare for work the next day—some by the river and others by the roadway. The poor people were almost overcome with grief, many of them shedding tears, but none dared to disobey the orders of their master. On the morning of Easter Monday, while the church bells were calling the inhabitants to religious services, and while every one else was about to enjoy a holiday, the unfortunate serfs started for the field to plough. Michael arose rather late and took a walk about the farm. The domestic servants were through with their work and had dressed themselves for the day, while Michael’s wife and their widowed daughter (who was visiting them, as was her custom on holidays) had been to church and returned. A steaming samovar awaited them, and they began to drink tea with Michael, who, after lighting his pipe, called the elder to him. “Well,” said the superintendent, “have you ordered the moujiks to plough to-day?” “Yes, sir, I did,” was the reply. “Have they all gone to the field?” “Yes, sir; all of them. I directed them myself where to begin.” “That is all very well. You gave the orders, but are they ploughing? Go at once and see, and you may tell them that I shall be there after dinner. I shall expect to find one and a half acres done for every two ploughs, and the work must be well done; otherwise they shall be severely punished, notwithstanding the holiday.” “I hear, sir, and obey.” The elder started to go, but Michael called him back. After hesitating for some time, as if he felt very uneasy, he said: “By the way, listen to what those scoundrels say about me. Doubtless some of them will curse me, and I want you to report the exact words. I know what villains they are. They don’t find work at all pleasant. They would rather lie down all day and do nothing. They would like to eat and drink and make merry on holidays, but they forget that if the ploughing is not done it will soon be too late. So you go and listen to what is said, and tell it to me in detail. Go at once.” “I hear, sir, and obey.” Turning his back and mounting his horse, the elder was soon at the field where the serfs were hard at work. It happened that Michael’s wife, a very good-hearted woman, overheard the conversation which her husband had just been holding with the elder. Approaching him, she said: “My good friend, Mishinka [diminutive of Michael], I beg of you to consider the importance and solemnity of this holy-day. Do not sin, for Christ’s sake. Let the poor moujiks go home.” Michael laughed, but made no reply to his wife’s humane request. Finally he said to her: “You’ve not been whipped for a very long time, and now you have become bold enough to interfere in affairs that are not your own.” “Mishinka,” she persisted, “I have had a frightful dream concerning you. You had better let the moujiks go.” “Yes,” said he; “I perceive that you have gained so much flesh of late that you think you would not feel the whip. Lookout!” Rudely thrusting his hot pipe against her cheek, Michael chased his wife from the room, after which he ordered his dinner. After eating a hearty meal consisting of cabbage-soup, roast pig, meat-cake, pastry with milk, jelly, sweet cakes, and vodka, he called his woman cook to him and ordered her to be seated and sing songs, Simeonovitch accompanying her on the guitar. While the superintendent was thus enjoying himself to the fullest satisfaction in the musical society of his cook the elder returned, and, making a low bow to his superior, proceeded to give the desired information concerning the serfs. “Well,” asked Michael, “did they plough?” “Yes,” replied the elder; “they have accomplished about half the field.” “Is there no fault to be found?” “Not that I could discover. The work seems to be well done. They are evidently afraid of you.” “How is the soil?” “Very good. It appears to be quite soft.” “Well,” said Simeonovitch, after a pause, “what did they say about me? Cursed me, I suppose?” As the elder hesitated somewhat, Michael commanded him to speak and tell him the whole truth. “Tell me all,” said he; “I want to know their

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"The Candle Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 22 Feb. 2025. <https://www.literature.com/book/the_candle_3933>.

Discuss this The Candle book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In