Sundays of a Bourgeois Page #2

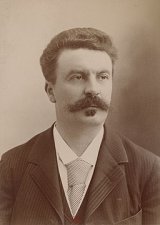

"Sundays of a Bourgeois" by Guy de Maupassant is a short story that explores the life of a wealthy bourgeois family in 19th-century France. The narrative delves into the monotony and superficiality of their Sunday routine, reflecting on themes of social class, materialism, and the emptiness of bourgeois life. Through vivid characterizations and keen observations, Maupassant critiques the moral and emotional vacuity that often accompanies affluence, offering a poignant commentary on the human condition and the nature of happiness.

Then he consulted his friends, showing them the fateful paper. One advised boxing. He immediately hunted up an instructor, and, on the first day, he received a punch in the nose which immediately took away all his ambition in this direction. Single-stick made him gasp for breath, and he grew so stiff from fencing that for two days and two nights he could not get sleep. Then a bright idea struck him. It was to walk, every Sunday, to some suburb of Paris and even to certain places in the capital which he did not know. For a whole week his mind was occupied with thoughts of the equipment which you need for these excursions; and on Sunday, the 30th of May, he began his preparations. After reading all the extraordinary advertisements which poor, blind and halt beggars distribute on the street corners, he began to visit the stores with the intention of looking about him only and of buying later on. First of all, he visited a so-called American shoe store, where heavy travelling shoes were shown him. The clerk brought out a kind of ironclad contrivance, studded with spikes like a harrow, which he claimed to be made from Rocky Mountain bison skin. He was so carried away with them that he would willingly have bought two pair, but one was sufficient. He carried them away under his arm, which soon became numb from the weight. He next invested in a pair of corduroy trousers, such as carpenters wear, and a pair of oiled canvas leggings. Then he needed a knapsack for his provisions, a telescope so as to recognize villages perched on the slope of distant hills, and finally, a government survey map to enable him to find his way about without asking the peasants toiling in the fields. Lastly, in order more comfortably to stand the heat, he decided to purchase a light alpaca jacket offered by the famous firm of Raminau, according to their advertisement, for the modest sum of six francs and fifty centimes. He went to this store and was welcomed by a distinguished-looking young man with a marvellous head of hair, nails as pink as those of a lady and a pleasant smile. He showed him the garment. It did not correspond with the glowing style of the advertisement. Then Patissot hesitatingly asked, “Well, monsieur, will it wear well?” The young man turned his eyes away in well-feigned embarrassment, like an honest man who does not wish to deceive a customer, and, lowering his eyes, he said in a hesitating manner: “Dear me, monsieur, you understand that for six francs fifty we cannot turn out an article like this for instance.” And he showed him a much finer jacket than the first one. Patissot examined it and asked the price. “Twelve francs fifty.” It was very tempting, but before deciding, he once more questioned the big young man, who was observing him attentively. “And—is that good? Do you guarantee it?” “Oh! certainly, monsieur, it is quite good! But, of course, you must not get it wet! Yes, it's really quite good, but you understand that there are goods and goods. It's excellent for the price. Twelve francs fifty, just think. Why, that's nothing at all. Naturally a twenty-five-franc coat is much better. For twenty-five francs you get a superior quality, as strong as linen, and which wears even better. If it gets wet a little ironing will fix it right up. The color never fades, and it does not turn red in the sunlight. It is the warmest and lightest material out.” He unfolded his wares, holding them up, shaking them, crumpling and stretching them in order to show the excellent quality of the cloth. He talked on convincingly, dispelling all hesitation by words and gesture. Patissot was convinced; he bought the coat. The pleasant salesman, still talking, tied up the bundle and continued praising the value of the purchase. When it was paid for he was suddenly silent. He bowed with a superior air, and, holding the door open, he watched his customer disappear, both arms filled with bundles and vainly trying to reach his hat to bow. M. Patissot returned home and carefully studied the map. He wished to try on his shoes, which were more like skates than shoes, owing to the spikes. He slipped and fell, promising himself to be more careful in the future. Then he spread out all his purchases on a chair and looked at them for a long time. He went to sleep with this thought: “Isn't it strange that I didn't think before of taking an excursion to the country?” During the whole week Patissot worked without ambition. He was dreaming of the outing which he had planned for the following Sunday, and he was seized by a sudden longing for the country, a desire of growing tender over nature, this thirst for rustic scenes which overwhelms the Parisians in spring time. Only one person gave him any attention; it was a silent old copying clerk named Boivin, nicknamed Boileau. He himself lived in the country and had a little garden which he cultivated carefully; his needs were small, and he was perfectly happy, so they said. Patissot was now able to understand his tastes and the similarity of their ideals made them immediately fast friends. Old man Boivin said to him: “Do I like fishing, monsieur? Why, it's the delight of my life!” Then Patissot questioned him with deep interest. Boivin named all the fish who frolicked under this dirty water—and Patissot thought he could see them. Boivin told about the different hooks, baits, spots and times suitable for each kind. And Patissot felt himself more like a fisherman than Boivin himself. They decided that the following Sunday they would meet for the opening of the season for the edification of Patissot, who was delighted to have found such an experienced instructor. FISHING EXCURSION The day before the one when he was, for the first time in his life, to throw a hook into a river, Monsieur Patissot bought, for eighty centimes, “How to Become a Perfect Fisherman.” In this work he learned many useful things, but he was especially impressed by the style, and he retained the following passage: “In a word, if you wish, without books, without rules, to fish successfully, to the left or to the right, up or down stream, in the masterly manner that halts at no difficulty, then fish before, during and after a storm, when the clouds break and the sky is streaked with lightning, when the earth shakes with the grumbling thunder; it is then that, either through hunger or terror, all the fish forget their habits in a turbulent flight. “In this confusion follow or neglect all favorable signs, and just go on fishing; you will march to victory!” In order to catch fish of all sizes, he bought three well-perfected poles, made to be used as a cane in the city, which, on the river, could be transformed into a fishing rod by a simple jerk. He bought some number fifteen hooks for gudgeon, number twelve for bream, and with his number seven he expected to fill his basket with carp. He bought no earth worms because he was sure of finding them everywhere; but he laid in a provision of sand worms. He had a jar full of them, and in the evening he watched them with interest. The hideous creatures swarmed in their bath of bran as they do in putrid meat. Patissot wished to practice baiting his hook. He took up one with disgust, but he had hardly placed the curved steel point against it when it split open. Twenty times he repeated this without success, and he might have continued all night had he not feared to exhaust his supply of vermin.

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Sundays of a Bourgeois Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 9 Mar. 2025. <https://www.literature.com/book/sundays_of_a_bourgeois_4108>.

Discuss this Sundays of a Bourgeois book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In