Paris Nights and Other Impressions of Places and People Page #9

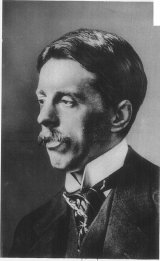

Enoch Arnold Bennett (27 May 1867 - 27 March 1931) was an English writer. He is best known as a novelist, but he also worked in other fields such as the theatre, journalism, propaganda and films. Bennett was born in a modest house in Hanley in the Potteries district of Staffordshire. Hanley was one of the Six Towns that were joined together at the beginning of the 20th century as Stoke-on-Trent and are depicted as "the Five Towns" in some of Bennett's novels. Enoch Bennett, his father, qualified as a solicitor in 1876, and the family moved to a larger house between Hanley and Burslem.

- Year:

- 1913

- 108,250 Views

“Ça y est?” asked the Tante, meaning--were the infants at last couched? “Ça y est” said the mother, with triumph, with relief, and yet also with a little regret. There was a nurse, but in practice she was only an under-nurse; the head-nurse was the mother. “Eh bien, mon petit Bennett,” the mother began, in a new tone, as if to indicate that she was no longer a mother, but a Parisienne, frivolous and challenging, “what there that is new?” “He is there,” said the Tante, interrupting. We heard the noise of the front-door, and by a common instinct we all rose and went into the hall. ***** The master of the home arrived. He entered like a gust of wind, and Marthe, the thin old parlourmaid, who had evidently been lying in wait for him, started back in alarm, but alarm half-simulated. My host, about the same age as his wife, was a doctor, specialising in the diseases of women and children, and he had his cabinet on the ground-floor of the same house. He was late, he was impatient to regain his hearth, he was proud of his industry; and the simple, instinctive joy of life sparkled in his eye. “Marie,” he cried to his wife. “I love thee!” And kissed her furiously on both cheeks. “It is well,” she responded, calmly smiling, with a sort of flirtatious condescension. “I tell thee I love thee!” he insisted, with his hands on her shoulders. “Tell me that thou lovest me!” “I love thee,” she said calmly. “It is very well!” he said, and swinging round to Marthe, giving her his hat. “Marthe, I love you.” And he caught her a smack on the shoulder. “Monsieur hurts me,” the spinster protested. “Go then! Go then!” said the Tante, as the beloved nephew directed his assault upon her in turn. She was grimly proud of him. He flattered her eye, for, even at his loosest, he had a professional distinction of deportment which her long-deceased husband, a wholesale tradesman, had probably lacked. “Well, my old one,” the host grasped my hand once more, “you cannot figure to yourself how it gives me pleasure to have you here!” His voice was rich with emotion. This man had the genius of friendship in a very high degree. His delight in the society of his friends was so intense and so candid that only the most inordinately conceited among them could have failed to be aware of an uncomfortable grave sense of unworthiness, could have failed to say to themselves fearfully: “He will find me out one day!” ***** The dining-room was large, and massively furnished, and lighted by one immense shaded lamp that hung low over the table. Among the heavily framed pictures was a magnificent Jules Dupré, belonging to the Tante. She had picked it up long ago at a sale for something like ten thousand francs, apparently while the dealers were looking the other way. It was a known picture, and one of the Tante’s satisfactions was that some dealer or other was always trying to relieve her of it, without the slightest success. She had a story, too, that on the day after the sale a Duchesse who affected Duprés had sent her footman offering to take the picture off her at a ten per cent, increase because it would make a pair with another magnificent Dupré already owned by the Duchesse. “Eh, well,” the widow of the tradesman had said to the footman, “you will tell Madame la Duchesse that if she wants my picture she had better come herself and inquire about it.” In the flat, the Dupré was one of the great pictures of the world. Safer to sneeze at the Venus de Milo than at that picture! Another favourite picture, also the property of Tante, was one by a living and super-modern painter, an acquaintance of another nephew of hers. I do not think she much cared for it, or that she cared much for any pictures. She had bought it by a benevolent caprice. “What would you? He had not the sou. C’est un très gentil garçon, of a great talent, but he was eating all his money with women--with those birds that you know. And one day it may be worth its price.” What always interested me most in the furniture of that dining-room was not the pictures, nor the ample plate, nor the edifices called sideboards, etc., but the apron of Marthe, who served. A plain, unstarched, white apron, without a bib--an apron that no English parlourmaid would have deigned to wear; but of such fine linen, and all the exactly geometric creases of its folding visible to the eye as Marthe passed round and round our four chairs! Whenever I saw that apron I could see linen-chests, and endless supplies of linen, and Tante and Marthe fussing over them on quiet afternoons. And it went so well with her dark-blue shiny frock! When Tante had joined her nephew’s household she had brought with her Marthe, already old in her service. These two women were devoted to each other, each in her own way. “Arrive then, with that sauce, vieille folle!” Tante would command; and Marthe, pursing her lips, would defend herself with a “Mais madame--!” There was no high invisible wall between Marthe and her employers. One was not worried, as one would have been in England, by the operation of the detestable and barbaric theory that Marthe was an automaton, inaccessible to human emotions. I remember seeing in the work-basket of the wife of a wealthy English socialist a little manual of advice to domestic servants upon their deportment, and I remember this: “Learn to control your voice, and always speak in a low voice. Never show by your demeanour that you have heard any remark which is not addressed to you.” I wonder what Marthe, who had never worn a cap, nor perhaps seen one, would have thought of the manual, which possibly was written by a distressed gentlewoman in order to earn a few shillings. Martha could smile. She could even laugh and answer back--but within limits. We had not to pretend that Marthe consisted merely of two ministering hands animated by a brain, but without a soul. In France a servant works longer and harder than in England, but she is permitted the constant use of a soul. A simple but an expensive dinner, for these people were the kind of people that, desiring only the best, were in a position to see that they had it, and accepted the cost as a matter of course. Moreover, they knew what the best was, especially the Tante. They knew how to buy. The chief dish was just steak. But what steak! What a thickness of steak and what tenderness! A whole cow had lived under the most approved conditions, and died a violent death, and the very essence of the excuse for it all lay on a blue and white dish in front of the hostess. Cost according! Steak; but better steak could not be had in the world! And the consciousness of this fact was on the calm benignant face of the hostess and on the vivacious ironic face of the Tante. So with the fruits of the earth, so with the wine. And the simple, straightforward distribution of the viands seemed to suit well their character. Into that flat there had not yet penetrated the grand modern principle that the act of carving is an obscene act, an act to be done shamefully in secret, behind the backs of the delicate impressionable. No! The dish of steak was planted directly in front of the hostess, under her very nose, and beyond the dish a pile of four plates; and, brazenly brandishing her implements, the Parisienne herself cut the titbits out of the tit-bit, and deposited them on plate after plate, which either Marthe took or we took ourselves, at hazard. Further, there was no embarrassment of multitudinous assorted knives and forks and spoons. With each course the diner received the tools necessary for that course. Between courses, if he wanted a toy for his fingers, he had to be content with a crust.

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Paris Nights and Other Impressions of Places and People Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 12 Mar. 2025. <https://www.literature.com/book/paris_nights_and_other_impressions_of_places_and_people_110>.

Discuss this Paris Nights and Other Impressions of Places and People book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In