Paris Nights and Other Impressions of Places and People Page #13

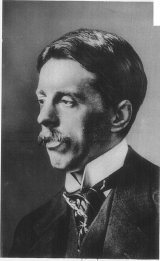

Enoch Arnold Bennett (27 May 1867 - 27 March 1931) was an English writer. He is best known as a novelist, but he also worked in other fields such as the theatre, journalism, propaganda and films. Bennett was born in a modest house in Hanley in the Potteries district of Staffordshire. Hanley was one of the Six Towns that were joined together at the beginning of the 20th century as Stoke-on-Trent and are depicted as "the Five Towns" in some of Bennett's novels. Enoch Bennett, his father, qualified as a solicitor in 1876, and the family moved to a larger house between Hanley and Burslem.

- Year:

- 1913

- 106,005 Views

***** The supper-restaurants were visited earlier and were much more crowded than usual on that night. It was as though the influence of the trial had been aphrodisiacal. Or it may have been that the men and women of pleasure wished to receive the verdict in circumstances worthy of its importance in the annals of pleasure. Or it may have been that dinner had been deranged by the excitations connected with the trial and that people felt honestly hungry. I went into one of these restaurants, in a square whose buildings are embroidered with inviting letters of fire until dawn every morning throughout the year. A stern attendant took me up in a lift, and instantly I had quitted the sternness of the lift I was in another atmosphere. There was the bar, and there the illustrious English barman, drunk. For in these regions the barman must always be English and a little drunk. The barman knows everybody, and not to know his Christian name and the feel of his hand is to be nobody. This barman is a Parisian celebrity. But let an accident or a misadventure disqualify him from his work, and he will be forgotten utterly in less than a week. And in his martyred old age he will certainly recount to charitable acquaintances, who find him ineffably tedious, how he was barman at the unique Restaurant Lepic in the old days when fun was really fun, and the most appalling iniquity was openly tolerated by the police. The bar and the barman and the cloak-room attendant (another man of genius) are only the prelude to the great supper-hall, which is simply and completely dazzling, with its profuse festoons of electric bulbs, its innumerable naked shoulders, arms, and bosoms, its fancy costumes, its bald heads, its music, clatter, and tinkle, and its desperate gaiety. To go into it is like going into a furnace of sensuality. It can be likened to nothing but an orange-lit scene of Roman debauch in a play written and staged by Mr. Hall Caine. One feels that one has been unjust in one’s attitude to Mr. Hall Caine’s claims as a realist. Although the restaurant will positively not hold any more revellers, more revellers insist on coming in, and fresh tables are produced by conjuring and placed for them between other tables, until the whole mass of wood and flesh is wedged tight together and waiters have to perform prodigies of insinuation. The effect of these multitudinous wasters is desolating, and even pathetic. It is the enormous stupidity of the mass that is pathetic, and its secret tedium that is desolating. At their wits’ end how to divert themselves, these bald heads pass the time in capers more antique and fatuous than were ever employed at a village wedding. Some of them find distraction in monstrous gorging--and beefsteaks and fried potatoes and spicy sauces go down their throats in a way to terrorise the arthritic beholder. Others merely drink. Some quarrel, with the boneless persistency of intoxication. One falls humorously under a table, and is humorously fished up by the red-coated leader of the orchestra: it is a marked success of esteem. Many are content to caress the bright odalisques with fond, monotonous vacuity. A few of these odalisques, and the waiters, alone save the spectacle from utter humiliation. The waiters are experts engaged in doing their job. The industry of each night leaves them no energy for dissoluteness. They are alert and determined. Their business is to make stupidity as lavish as possible, and they succeed. To see them surveying with cold statistical glances the field of their operations, to listen to their indestructible politeness, to divine the depth of their concealed scorn--this is a pleasure. And some of the odalisques are beautiful. Fine women in the sight of heaven! They too are experts, with the hard preoccupation of experts. They are at work; and this is the battle of life. They inspire respect. It is--it is the dignity of labour. [Illustration: 0099] Suddenly it is announced that the jury at the Palace are about to deliver their verdict. Nobody knows how the news has come, nor even who first spoke it in the restaurant. But there it is. Humorous guffaws of relief are vented. The fever of the place becomes acute, with a decided influence on the consumption of champagne. The accused lady is toasted again and again. Of course, she had been, throughout, the solid backbone of the chatter; but now she was all the chatter. And everybody recounted again to everybody else every suggestive rumour of her iniquity that had appeared in any newspaper for months past. She was tried over again in a moment, and condemned and insulted and defended, and consistently honoured with libations. She had never been more truly heroic, more legendary, than she was then. The childlike company loudly demanded the verdict, with their tongues and with their feet. A beautiful young girl of about eighteen, the significant features of whose attire were long black stockings and a necklace, said to a gentleman who was helping her to eat a vast entrecote and to drink champagne: “If it comes not soon, it will be too late.” “The verdict?” said the fatuous swain. “How?--too late?” “I shall be too drunk,” said the girl, apparently meaning that she would be too drunk to savour the verdict and to get joy from it. She spoke with mournful and slightly disgusted certainty, as though anticipating a phenomenon which was absolutely regular and absolutely inevitable. And then, on a table near the centre of the room, instead of plates and glasses appeared a child-dancer who might have been Spanish or Creole, but who probably had never been out of Montmartre. This child seemed to be surrounded by her family seated at the table--by her mother and her aunts and a cousin or so, all with simple and respectable faces, naïvely proud of and pleased with the child. From their expressions, the child might have been cutting bread and butter on the table instead of dancing. The child danced exquisitely, but her performance could not moderate the din. It was a lovely thing gloriously wasted. The one feature of it that was not wasted on the intelligence of the company was the titillating contrast between the little girl’s fresh infancy and the advanced decomposition of her environment. She ceased, and disappeared into her family. The applause began, but it was mysteriously and swiftly cut short. Why did every one by a simultaneous impulse glance eagerly in the direction of the door? Why was the hush so dramatic? A voice--whose?--cried near the doorway: “Acquittée!” And all cried triumphantly: “Acquittée! Acquittée! Acquittée! Acquittée!” Happy, boisterous Bedlam was created and let loose. Even the waiters forgot themselves. The whole world stood up, stood on chairs, or stood on tables; and shouted, shrieked, and whistled. But the boneless drunkards were still quarrelling, and one bald head had retained sufficient presence of mind to wear a large oyster-shell facetiously for a hat. And then the orchestra, inspired, struck into a popular refrain of the moment, perfectly apposite. And all sang with right good-will:

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Paris Nights and Other Impressions of Places and People Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2024. Web. 24 Dec. 2024. <https://www.literature.com/book/paris_nights_and_other_impressions_of_places_and_people_110>.

Discuss this Paris Nights and Other Impressions of Places and People book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In