Paris Nights and Other Impressions of Places and People Page #11

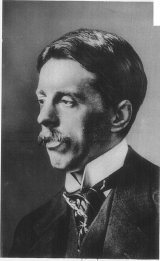

Enoch Arnold Bennett (27 May 1867 - 27 March 1931) was an English writer. He is best known as a novelist, but he also worked in other fields such as the theatre, journalism, propaganda and films. Bennett was born in a modest house in Hanley in the Potteries district of Staffordshire. Hanley was one of the Six Towns that were joined together at the beginning of the 20th century as Stoke-on-Trent and are depicted as "the Five Towns" in some of Bennett's novels. Enoch Bennett, his father, qualified as a solicitor in 1876, and the family moved to a larger house between Hanley and Burslem.

- Year:

- 1913

- 105,982 Views

“I pray thee,” said the mother. “Go at once. And do not excite them.” “I think I’ll go with you,” I said. “My little Bennett,” the mother leaned towards me, “I supplicate you--at this hour--” “But naturally he will come with me!” the host cried obstreperously. We went, down a long narrow passage. There they were in their beds, the children, in a small bedroom divided into two by a low screen of ribbed glass, the boy on one side and the girl on the other. The window gave on to a small subsidiary courtyard. Through the half-drawn curtains the lighted windows of rooms opposite could be discerned, rising, storey after storey, up out of sight. A night-light burned on a table. The nurse stood apart, at the door. The children were lively, but pale. They had begun to go to school, and, except the journey to and from school, they seemed to have almost no outdoor exercise. No garden was theirs. The hall and the passages were their sole playground. And all the best part of their lives was passed between walls in a habitation twenty-five or thirty feet above ground, in the middle of Paris. Yet they were very well. The doctor did not romp with them. No! He simply and candidly caressed them, girl and boy, in turn, calling them passionately by the most beautiful names, burying his head in the bedclothes, and fondling their wild hair. He then entreated them, with genuine humility, to compose themselves for sleep, and parted last from the girl. “She is exquisite--exquisite!” he murmured to me ecstatically, as we returned up the passage from this excursion. She was. ***** In the small sitting-room the cousin was offering to the Tante some information of a political nature. The Tante kept a judicious eye on everything in Paris. . “What!” The host protested vociferously. “He is again in his politics! Cousin, I supplicate thee--” A good deal of supplication went on there. The host did succeed in stopping politics. With all the weight of his vivacious good-nature he bore politics down. The fact was, he had a real objection to politics, having convinced himself that they were permanently unclean in France. It was not the measures that he objected to, but the men--all of them with scarcely an exception--as cynical adventurers. On this point he was passionate. Politics were incurably futile, horribly assommant. He would not willingly allow them to soil his hearth. “What hast thou done lately?” he asked of the cousin, changing the subject. And the talk veered to public amusements. The cousin had been “distracting himself” amid his sentimental misadventures, by much theatre-going. They all, except the Tante, went very regularly to the theatres and to the operas. And not only that, but to concerts, exhibitions, picture-shows, services in the big churches, and every kind of diversion frequented by people in easy circumstances and by artists. There was little that they missed. They exhibited no special taste or knowledge in any art, but leaned generally to the best among that which was merely fashionable. They took seriously nearly every craftsman who, while succeeding, kept his dignity and refrained from being a mountebank. Thus, they were convinced that dramatists like Edmond Rostand and Henri Lavedan, actors and actresses like Le Bargy and Cécile Sorel, painters like Edouard Détaille and La Gandara, composers like Massenet and Charpentier, critics like Adolphe Brisson and Francis Chevassu, novelists like René Bazin and Daniel Lesueur, poets like Jean Riche-pin and Abel Bonnard, were original and first-class, and genuinely important in the history of their respective arts. On the other hand their attitude towards the real innovators and shapers of the future was timidly, but honestly, antipathetic. And they could not, despite any theorising to the contrary, bring themselves to take quite seriously any artist who had not been consecrated by public approval. With the most charming grace they would submit to be teased about this, but it would have been impossible to tease them out of it. And there was always a slight uneasiness in the air when they and I came to grips in the discussion of art. I could almost hear the shrewd Tante saying to herself: “What a pity this otherwise sane and safe young man is an artist!” “Figure to yourself,” the host would answer me with an adorable, affectionate mien of apology, when I asked his opinion of a new work by Maurice Ravel, heard on a Sunday afternoon, “Figure to yourself that we scarcely liked it.” And with the same mien, of a very fashionable comedy in which Lavedan, Le Bargy, and Julia Bartet had combined to create a terrific success at the Théâtre Français: “Figure to yourself, it was truly very nice, after all! Of course one might say.. . .” The truth was, it had carried them off their feet. Upon my soul I think I liked them the better for it all. And, in talking to them, I understood a little better the real and solid basis upon which rests all that overwhelming, complex, expensive apparatus of artistic diversions laid out for the public within a mile radius of the Place de l’Opéra. There is a public, a genuine public, which desires ardently to be amused and which will handsomely put down the money for its amusement. And it is never tired, never satiated. The artist, who seldom pays, is apt to wonder if any considerable body of persons pay, is apt to regard the commercial continuance of art as a sort of inexplicable miracle. But these people paid. They always paid, and richly. And there were whole streets of large houses full of other people who shared their tastes and their habits, if not their extreme attractiveness. ***** I wondered where we should be without them, we artists, as I took leave of them at something after midnight. My good friend, the melancholy cousin, had departed. Tante had gone to bed, though she protested she never slept. We had been drinking weak tea as we wandered about the dining-room. And now I, obdurate against the host’s supplications not to desert them so early, was departing too. At the door the hostess lighted a little taper, and gave it to me. And when the door was opened they moderated their caressing voices; for a dozen other domestic interiors, each intricate and complete, gave on the resounding staircase. And with my little taper I descended through the silence and the darkness of the staircase. And at the bottom I halted in the black entrance way, and summoned the concierge out of his sleep to release the catch of the small door within the great portals. There was a responsive click immediately, and in the blackness a sudden gleam from the boulevard. The concierge and his wife, living for ever sunless in a room and a half beneath all those other interiors, were throughout the night at the mercy of a call, mine or another’s. “Curious existence!” I thought, as my shutting of the door echoed about the building, and I stepped into the illumination of the boulevard. “The concierge is necessary to them. And without the equivalent of such as they, such as I could not possess even a decent overcoat!” On the façade of the house every outer casement was shut. Not a sign of life in it.

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Paris Nights and Other Impressions of Places and People Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2024. Web. 23 Dec. 2024. <https://www.literature.com/book/paris_nights_and_other_impressions_of_places_and_people_110>.

Discuss this Paris Nights and Other Impressions of Places and People book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In