On Popular Education Page #12

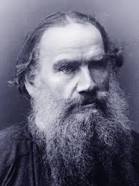

"On Popular Education" is a thought-provoking essay by Leo Tolstoy in which the renowned Russian author explores the role of education in shaping individuals and society. Written in 1862, Tolstoy critiques the existing educational systems of his time, advocating for a more accessible, practical, and moral approach to learning. He emphasizes the importance of fostering critical thinking and moral values over rote memorization, urging educators to nurture the innate curiosity of learners. Tolstoy's reflections serve as a powerful call for a more humane and equitable educational framework that empowers individuals to contribute meaningfully to society.

themselves, or to the parents who send the children to school, and so the answer to the question what the children are to be taught in a popular school can be got only from the masses. But, perhaps, we shall say that we, as highly cultured people, must not submit to the demands of the rude masses and that we must teach the masses what to wish. Thus many think, but to that I can give this one answer: give us a firm, incontrovertible foundation why this or that is chosen by you, show me a society in which the two diametrically opposed views on education do not exist among the highly cultured people; where it is not eternally repeated that if education falls into the hands of the clergy, the masses are educated in one sense, and if education falls into the hands of the progressists, the people are educated in another sense,--show me a state of society where that does not exist, and I will agree with you. So long as that does not exist, there is no criterion except the freedom of the learner, where, in matters of the popular school, the place of the learning children is taken by their parents, that is, by the needs of the masses. These needs are not only definite, quite clear, and everywhere the same throughout Russia, but also so intelligent and broad that they include all the most diversified demands of the people who are debating what the masses ought to be taught. These needs are: the knowledge of Russian and Church-Slavic reading, and calculation. The masses everywhere and always regard the natural sciences as useless trifles. Their programme is remarkable not only by its unanimity and firm definiteness, but, in my opinion, also by the breadth of its demands and the correctness of its view. The masses admit two spheres of knowledge, the most exact and the least subject to vacillation from a diversity of views,--the languages and mathematics; everything else they regard as trifles. I think that the masses are quite correct,--in the first place, because in this knowledge there can be no half information, no falseness, which they cannot bear, and, in the second, because the sphere of those two kinds of knowledge is immense. Russian and Church-Slavic grammar and calculation, that is, the knowledge of one dead and one living language, with their etymological and syntactical forms and their literatures, and arithmetic, that is, the foundation of all mathematics, form their programme of knowledge, which, unfortunately, but the rarest of the cultured class possess. In the third place, the masses are right, because by this programme they will be taught in the primary school only what will open to them the more advanced paths of knowledge, for it is evident that the thorough knowledge of two languages and their forms, and, in addition to them, of arithmetic, completely opens the paths to an independent acquisition of all other knowledge. The masses, as though feeling the false relation to them, when they are offered incoherent scraps of all kinds of information, repel that lie from themselves, and say: "I need know but this much,--the church language and my own and the laws of the numbers, but that other knowledge I will take myself if I want it." Thus, if we admit freedom as the criterion of what is to be taught, the programme of the popular schools is clearly and firmly defined, until the time when the masses shall express some new demands. Church-Slavic and Russian and arithmetic to their highest possible stages, and nothing else but that. That is the determination of the limits of the programme of the popular school, which, however, does not presume that all three subjects be introduced systematically. With such a programme the attainment of symmetrical results in all three subjects would naturally be desirable; but it cannot be said that the predominance of one subject over another would be injurious. The problem consists only in keeping within the limits of the programme. It may happen that from the demands of the parents, and especially from the knowledge of the teacher, this or that subject will be more prominent,--with a clerical person the Church-Slavic language, with a teacher from a county school--either Russian or arithmetic; in all these cases the demands of the masses will be satisfied, and the instruction will not depart from its fundamental criterion. The second part of the question, how to teach, that is, how to discover which method is the best, has remained just as unsolved. Just as in the first part of the question of what to teach, the assumption that on the basis of reflections it is possible to build a programme of instruction leads to contradictory schools, so it is also with the question as to how to teach. Let us take the very first stage of the teaching of reading. One asserts that it is easier to teach so from cards; another--according to the b, v system; a third--according to Korf; a fourth--according to the be, ve, ge system, and so forth. It is said that the nuns teach reading in six weeks by the buki-az--ba system. And every teacher, convinced of the superiority of his method, proves this superiority either by the fact that he teaches with it faster than others, or by reflections of the character which Mr. Bunákov and the German pedagogues adduce. At the present time, when there are thousands of examples, we ought to know precisely by what to be guided in our choice. Neither theory, nor reflections, nor even the results of instruction can show this completely. Education and instruction are generally considered in the abstract, that is, the question is discussed how in the best and easiest manner to produce a certain act of instruction on a certain subject (whether it be one child or a mass of children). This view is quite faulty. All education and instruction can be viewed only as a certain relation of two persons or of two groups of persons having for their aim education or instruction. This definition, more general than all the other definitions, has special reference to popular education, where the question is the education of an immense number of persons, and where there can be no question about an ideal education. In general, with the popular education we cannot put the question, "How is the best education to be given?" just as with the question of the nutrition of the masses we cannot ask how the most nutritious and best loaf is to be baked. The question has to be put like this: "How is the best relation to be established between given people who want to learn and others who want to teach?" or, "How is the best bread to be made from given bolted flour?" Consequently the question of how to teach and what is the best method is a question of what will be the best relation between teacher and pupil. Nobody, I suppose, will deny that the best relation between teacher and pupil is that of naturalness, and that the contrary relation is that of

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"On Popular Education Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 24 Feb. 2025. <https://www.literature.com/book/on_popular_education_3979>.

Discuss this On Popular Education book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In