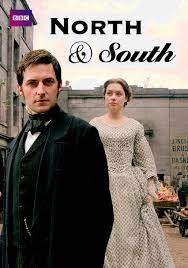

North and South Page #38

North and South is a social novel published in 1854 by English writer Elizabeth Gaskell. With Wives and Daughters and Cranford, it is one of her best-known novels and was adapted for television three times. The 2004 version renewed interest in the novel and attracted a wider readership.

“Does it make the town very rough?” asked Margaret. “Of course it does. But surely you are not a coward, are you? Milton is not the place for cowards. I have known the time when I have had to thread my way through a crowd of white, angry men, all swearing they would have Makinson’s blood as soon as he ventured to show his nose out of his factory; and he, knowing nothing of it, some one had to go and tell him, or he was a dead man; and it needed to be a woman,--so I went. And when I got in, I could not get out. It was as much as my life was worth. So I went up to the roof, where there were stones piled ready to drop on the heads of the crowd, if they tried to force the factory doors. And I would have lifted those heavy stones, and dropped them with as good an aim as the best man there, but that I fainted with the heat I had gone through. If you live in Milton, you must learn to have a brave heart, Miss Hale.” “I would do my best,” said Margaret rather pale. “I do not know whether I am brave or not till I am tried; but I am afraid I should be a coward.” “South country people are often frightened by what our Darkshire men and women only call living and struggling. But when you’ve been ten years among a people who are always owing their betters a grudge, and only waiting for an opportunity to pay it off, you’ll know whether you are a coward or not, take my word for it.” Mr. Thornton came that evening to Mr. Hale’s. He was shown up into the drawing-room, where Mr. Hale was reading aloud to his wife and daughter. “I am come partly to bring you a note from my mother, and partly to apologise for not keeping to my time yesterday. The note contains the address you asked for; Dr. Donaldson.” “Thank you!” said Margaret, hastily, holding out her hand to take the note, for she did not wish her mother to hear that they had been making any inquiry about a doctor. She was pleased that Mr. Thornton seemed immediately to understand her feeling; he gave her the note without another word of explanation. Mr. Hale began to talk about the strike. Mr. Thornton’s face assumed a likeness to his mother’s worst expression, which immediately repelled the watching Margaret. “Yes; the fools will have a strike. Let them. It suits us well enough. But we gave them a chance. They think trade is flourishing as it was last year. We see the storm on the horizon and draw in our sails. But because we don’t explain our reasons, they won’t believe we’re acting reasonably. We must give them line and letter for the way we choose to spend or save our money. Henderson tried a dodge with his men, out at Ashley, and failed. He rather wanted a strike; it would have suited his book well enough. So when the men came to ask for the five per cent. they are claiming, he told ’em he’d think about it, and give them his answer on the pay day; knowing all the while what his answer would be, of course, but thinking he’d strengthen their conceit of their own way. However, they were too deep for him, and heard something about the bad prospects of trade. So in they came on the Friday, and drew back their claim, and now he’s obliged to go on working. But we Milton masters have to-day sent in our decision. We won’t advance a penny. We tell them we may have to lower wages; but can’t afford to raise. So here we stand, waiting for their next attack.” “And what will that be?” asked Mr. Hale. “I conjecture a simultaneous strike. You will see Milton without smoke in a few days, I imagine, Miss Hale.” “But why,” asked she, “could you not explain what good reason you had for expecting a bad trade? I don’t know whether I use the right words, but you will understand what I mean.” “Do you give your servants reasons for your expenditure, or your economy in the use of your own money? We, the owners of capital, have a right to choose what we will do with it.” “A human right,” said Margaret, very low. “I beg your pardon, I did not hear what you said.” “I would rather not repeat it,” said she; “it related to a feeling which I do not think you would share.” “Won’t you try me?” pleaded he; his thoughts suddenly bent upon learning what she had said. She was displeased with his pertinacity, but did not choose to affix too much importance to her words. “I said you had a human right. I meant that there seemed no reason but religious ones, why you should not do what you like with your own.” “I know we differ in our religious opinions; but don’t you give me credit for having some, though not the same as yours?” He was speaking in a subdued voice, as if to her alone. She did not wish to be so exclusively addressed. She replied out in her usual tone: “I do not think that I have any occasion to consider your special religious opinions in the affair. All I meant to say is, that there is no human law to prevent the employers from utterly wasting or throwing away all their money, if they choose; but that there are passages in the Bible which would rather imply--to me at least--that they neglected their duties as stewards if they did so. However, I know so little about strikes and rate of wages, and capital, and labour, that I had better not talk to a political economist like you.” “Nay, the more reason,” said he eagerly. “I shall only be too glad to explain to you all that may seem anomalous or mysterious to a stranger; especially at a time like this, when our doings are sure to be canvassed by every scribbler who can hold a pen.” “Thank you,” she answered, coldly. “Of course, I shall apply to my father in the first instance for any information he can give me, if I get puzzled with living here amongst this strange society.” “You think it strange. Why?” “I don’t know--I suppose because, on the very face of it, I see two classes dependent on each other in every possible way, yet each evidently regarding the interests of the other as opposed to their own: I never lived in a place before where there were two sets of people always running each other down.” “Who have you heard running the masters down? I don’t ask who you have heard abusing the men; for I see you persist in misunderstanding what I said the other day. But who have you heard abusing the masters?” Margaret reddened; then smiled as she said, “I am not fond of being catechised. I refuse to answer your question. Besides, it has nothing to do with the fact. You must take my word for it, that I have heard some people, or, it may be, only some one of the workpeople speak as though it were the interest of the employers to keep them from acquiring money--that it would make them too independent if they had a sum in the savings’ bank.” “I dare say it was that man Higgins who told you all this,” said Mrs. Hale. Mr. Thornton did not appear to hear what Margaret evidently did not wish him to know. But he caught it nevertheless. “I heard, moreover, that it was considered to the advantage of the masters to have ignorant workmen--not hedge-lawyers, as Captain Lennox

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"North and South Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2024. Web. 26 Nov. 2024. <https://www.literature.com/book/north_and_south_1443>.

Discuss this North and South book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In