Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl Page #29

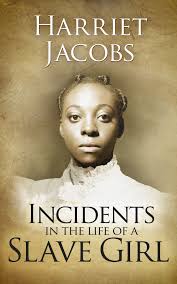

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, written by herself is an autobiography by Harriet Jacobs, a mother and fugitive slave, published in 1861 by L. Maria Child, who edited the book for its author. Jacobs used the pseudonym Linda Brent.

My plan was to conceal myself at the house of a friend, and remain there a few weeks till the search was over. My hope was that the doctor would get discouraged, and, for fear of losing my value, and also of subsequently finding my children among the missing, he would consent to sell us; and I knew somebody would buy us. I had done all in my power to make my children comfortable during the time I expected to be separated from them. I was packing my things, when grandmother came into the room, and asked what I was doing. "I am putting my things in order," I replied. I tried to look and speak cheerfully; but her watchful eye detected something beneath the surface. She drew me towards her, and asked me to sit down. She looked earnestly at me, and said, "Linda, do you want to kill your old grandmother? Do you mean to leave your little, helpless children? I am old now, and cannot do for your babies as I once did for you." I replied, that if I went away, perhaps their father would be able to secure their freedom. "Ah, my child," said she, "don't trust too much to him. Stand by your own children, and suffer with them till death. Nobody respects a mother who forsakes her children; and if you leave them, you will never have a happy moment. If you go, you will make me miserable the short time I have to live. You would be taken and brought back, and your sufferings would be dreadful. Remember poor Benjamin. Do give it up, Linda. Try to bear a little longer. Things may turn out better than we expect." My courage failed me, in view of the sorrow I should bring on that faithful, loving old heart. I promised that I would try longer, and that I would take nothing out of her house without her knowledge. Whenever the children climbed on my knee, or laid their heads on my lap, she would say, "Poor little souls! what would you do without a mother? She don't love you as I do." And she would hug them to her own bosom, as if to reproach me for my want of affection; but she knew all the while that I loved them better than my life. I slept with her that night, and it was the last time. The memory of it haunted me for many a year. On Monday I returned to the plantation, and busied myself with preparations for the important day. Wednesday came. It was a beautiful day, and the faces of the slaves were as bright as the sunshine. The poor creatures were merry. They were expecting little presents from the bride, and hoping for better times under her administration. I had no such hopes for them. I knew that the young wives of slaveholders often thought their authority and importance would be best established and maintained by cruelty; and what I had heard of young Mrs. Flint gave me no reason to expect that her rule over them would be less severe than that of the master and overseer. Truly, the colored race are the most cheerful and forgiving people on the face of the earth. That their masters sleep in safety is owing to their superabundance of heart; and yet they look upon their sufferings with less pity than they would bestow on those of a horse or a dog. I stood at the door with others to receive the bridegroom and bride. She was a handsome, delicate-looking girl, and her face flushed with emotion at sight of her new home. I thought it likely that visions of a happy future were rising before her. It made me sad; for I knew how soon clouds would come over her sunshine. She examined every part of the house, and told me she was delighted with the arrangements I had made. I was afraid old Mrs. Flint had tried to prejudice her against me, and I did my best to please her. All passed off smoothly for me until dinner time arrived. I did not mind the embarrassment of waiting on a dinner party, for the first time in my life, half so much as I did the meeting with Dr. Flint and his wife, who would be among the guests. It was a mystery to me why Mrs. Flint had not made her appearance at the plantation during all the time I was putting the house in order. I had not met her, face to face, for five years, and I had no wish to see her now. She was a praying woman, and, doubtless, considered my present position a special answer to her prayers. Nothing could please her better than to see me humbled and trampled upon. I was just where she would have me--in the power of a hard, unprincipled master. She did not speak to me when she took her seat at table; but her satisfied, triumphant smile, when I handed her plate, was more eloquent than words. The old doctor was not so quiet in his demonstrations. He ordered me here and there, and spoke with peculiar emphasis when he said "your mistress." I was drilled like a disgraced soldier. When all was over, and the last key turned, I sought my pillow, thankful that God had appointed a season of rest for the weary. The next day my new mistress began her housekeeping. I was not exactly appointed maid of all work; but I was to do whatever I was told. Monday evening came. It was always a busy time. On that night the slaves received their weekly allowance of food. Three pounds of meat, a peck of corn, and perhaps a dozen herring were allowed to each man. Women received a pound and a half of meat, a peck of corn, and the same number of herring. Children over twelve years old had half the allowance of the women. The meat was cut and weighed by the foreman of the field hands, and piled on planks before the meat house. Then the second foreman went behind the building, and when the first foreman called out, "Who takes this piece of meat?" he answered by calling somebody's name. This method was resorted to as a means of preventing partiality in distributing the meat. The young mistress came out to see how things were done on her plantation, and she soon gave a specimen of her character. Among those in waiting for their allowance was a very old slave, who had faithfully served the Flint family through three generations. When he hobbled up to get his bit of meat, the mistress said he was too old to have any allowance; that when niggers were too old to work, they ought to be fed on grass. Poor old man! He suffered much before he found rest in the grave.

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 26 Feb. 2025. <https://www.literature.com/book/incidents_in_the_life_of_a_slave_girl_947>.

Discuss this Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In