Cranford Page #21

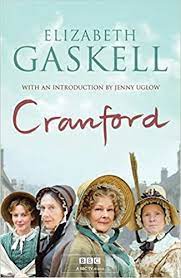

Cranford is an episodic novel by the English writer Elizabeth Gaskell. It first appeared in instalments in the magazine Household Words, then was published with minor revisions as a book with the title Cranford in 1853.

with him; for I knew I was good for little, and that my best work in the world was to do odd jobs quietly, and set others at liberty. But my father was a changed man.” “Did Mr Peter ever come home?” “Yes, once. He came home a lieutenant; he did not get to be admiral. And he and my father were such friends! My father took him into every house in the parish, he was so proud of him. He never walked out without Peter’s arm to lean upon. Deborah used to smile (I don’t think we ever laughed again after my mother’s death), and say she was quite put in a corner. Not but what my father always wanted her when there was letter-writing or reading to be done, or anything to be settled.” “And then?” said I, after a pause. “Then Peter went to sea again; and, by-and-by, my father died, blessing us both, and thanking Deborah for all she had been to him; and, of course, our circumstances were changed; and, instead of living at the rectory, and keeping three maids and a man, we had to come to this small house, and be content with a servant-of-all-work; but, as Deborah used to say, we have always lived genteelly, even if circumstances have compelled us to simplicity. Poor Deborah!” “And Mr Peter?” asked I. “Oh, there was some great war in India—I forget what they call it—and we have never heard of Peter since then. I believe he is dead myself; and it sometimes fidgets me that we have never put on mourning for him. And then again, when I sit by myself, and all the house is still, I think I hear his step coming up the street, and my heart begins to flutter and beat; but the sound always goes past—and Peter never comes. “That’s Martha back? No! I’ll go, my dear; I can always find my way in the dark, you know. And a blow of fresh air at the door will do my head good, and it’s rather got a trick of aching.” So she pattered off. I had lighted the candle, to give the room a cheerful appearance against her return. “Was it Martha?” asked I. “Yes. And I am rather uncomfortable, for I heard such a strange noise, just as I was opening the door.” “Where?” I asked, for her eyes were round with affright. “In the street—just outside—it sounded like”— “Talking?” I put in, as she hesitated a little. “No! kissing”— CHAPTER VII—VISITING ONE morning, as Miss Matty and I sat at our work—it was before twelve o’clock, and Miss Matty had not changed the cap with yellow ribbons that had been Miss Jenkyns’s best, and which Miss Matty was now wearing out in private, putting on the one made in imitation of Mrs Jamieson’s at all times when she expected to be seen—Martha came up, and asked if Miss Betty Barker might speak to her mistress. Miss Matty assented, and quickly disappeared to change the yellow ribbons, while Miss Barker came upstairs; but, as she had forgotten her spectacles, and was rather flurried by the unusual time of the visit, I was not surprised to see her return with one cap on the top of the other. She was quite unconscious of it herself, and looked at us, with bland satisfaction. Nor do I think Miss Barker perceived it; for, putting aside the little circumstance that she was not so young as she had been, she was very much absorbed in her errand, which she delivered herself of with an oppressive modesty that found vent in endless apologies. Miss Betty Barker was the daughter of the old clerk at Cranford who had officiated in Mr Jenkyns’s time. She and her sister had had pretty good situations as ladies’ maids, and had saved money enough to set up a milliner’s shop, which had been patronised by the ladies in the neighbourhood. Lady Arley, for instance, would occasionally give Miss Barkers the pattern of an old cap of hers, which they immediately copied and circulated among the élite of Cranford. I say the élite, for Miss Barkers had caught the trick of the place, and piqued themselves upon their “aristocratic connection.” They would not sell their caps and ribbons to anyone without a pedigree. Many a farmer’s wife or daughter turned away huffed from Miss Barkers’ select millinery, and went rather to the universal shop, where the profits of brown soap and moist sugar enabled the proprietor to go straight to (Paris, he said, until he found his customers too patriotic and John Bullish to wear what the Mounseers wore) London, where, as he often told his customers, Queen Adelaide had appeared, only the very week before, in a cap exactly like the one he showed them, trimmed with yellow and blue ribbons, and had been complimented by King William on the becoming nature of her head-dress. Miss Barkers, who confined themselves to truth, and did not approve of miscellaneous customers, throve notwithstanding. They were self-denying, good people. Many a time have I seen the eldest of them (she that had been maid to Mrs Jamieson) carrying out some delicate mess to a poor person. They only aped their betters in having “nothing to do” with the class immediately below theirs. And when Miss Barker died, their profits and income were found to be such that Miss Betty was justified in shutting up shop and retiring from business. She also (as I think I have before said) set up her cow; a mark of respectability in Cranford almost as decided as setting up a gig is among some people. She dressed finer than any lady in Cranford; and we did not wonder at it; for it was understood that she was wearing out all the bonnets and caps and outrageous ribbons which had once formed her stock-in-trade. It was five or six years since she had given up shop, so in any other place than Cranford her dress might have been considered passée. And now Miss Betty Barker had called to invite Miss Matty to tea at her house on the following Tuesday. She gave me also an impromptu invitation, as I happened to be a visitor—though I could see she had a little fear lest, since my father had gone to live in Drumble, he might have engaged in that “horrid cotton trade,” and so dragged his family down out of “aristocratic society.” She prefaced this invitation with so many apologies that she quite excited my curiosity. “Her presumption” was to be excused. What had she been doing? She seemed so over-powered by it I could only think that she had been writing to Queen Adelaide to ask for a receipt for washing lace; but the act which she so characterised was only an invitation she had carried to her sister’s former mistress, Mrs Jamieson. “Her former occupation considered, could Miss Matty excuse the liberty?” Ah! thought I, she has found out that double cap, and is going to rectify Miss Matty’s head-dress. No! it was simply to extend her invitation to Miss Matty and to me. Miss Matty bowed acceptance; and I wondered that, in the graceful action, she did not feel the unusual weight and extraordinary height of her head-dress. But I do not think she did, for she recovered her balance, and went on talking to Miss Betty in a kind, condescending manner, very different

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Cranford Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2024. Web. 24 Nov. 2024. <https://www.literature.com/book/cranford_1444>.

Discuss this Cranford book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In