Cranford Page #18

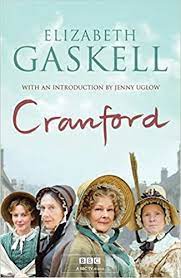

Cranford is an episodic novel by the English writer Elizabeth Gaskell. It first appeared in instalments in the magazine Household Words, then was published with minor revisions as a book with the title Cranford in 1853.

hall, just near enough the study-door, to catch the tone of my father’s voice. I could tell in a moment if all was going right, by her face. And it did go right for a long time.” “What went wrong at last?” said I. “That tiresome Latin, I dare say.” “No! it was not the Latin. Peter was in high favour with my father, for he worked up well for him. But he seemed to think that the Cranford people might be joked about, and made fun of, and they did not like it; nobody does. He was always hoaxing them; ‘hoaxing’ is not a pretty word, my dear, and I hope you won’t tell your father I used it, for I should not like him to think that I was not choice in my language, after living with such a woman as Deborah. And be sure you never use it yourself. I don’t know how it slipped out of my mouth, except it was that I was thinking of poor Peter and it was always his expression. But he was a very gentlemanly boy in many things. He was like dear Captain Brown in always being ready to help any old person or a child. Still, he did like joking and making fun; and he seemed to think the old ladies in Cranford would believe anything. There were many old ladies living here then; we are principally ladies now, I know, but we are not so old as the ladies used to be when I was a girl. I could laugh to think of some of Peter’s jokes. No, my dear, I won’t tell you of them, because they might not shock you as they ought to do, and they were very shocking. He even took in my father once, by dressing himself up as a lady that was passing through the town and wished to see the Rector of Cranford, ‘who had published that admirable Assize Sermon.’ Peter said he was awfully frightened himself when he saw how my father took it all in, and even offered to copy out all his Napoleon Buonaparte sermons for her—him, I mean—no, her, for Peter was a lady then. He told me he was more terrified than he ever was before, all the time my father was speaking. He did not think my father would have believed him; and yet if he had not, it would have been a sad thing for Peter. As it was, he was none so glad of it, for my father kept him hard at work copying out all those twelve Buonaparte sermons for the lady—that was for Peter himself, you know. He was the lady. And once when he wanted to go fishing, Peter said, ‘Confound the woman!’—very bad language, my dear, but Peter was not always so guarded as he should have been; my father was so angry with him, it nearly frightened me out of my wits: and yet I could hardly keep from laughing at the little curtseys Peter kept making, quite slyly, whenever my father spoke of the lady’s excellent taste and sound discrimination.” [Picture: Confound the woman] “Did Miss Jenkyns know of these tricks?” said I. “Oh, no! Deborah would have been too much shocked. No, no one knew but me. I wish I had always known of Peter’s plans; but sometimes he did not tell me. He used to say the old ladies in the town wanted something to talk about; but I don’t think they did. They had the St James’s Chronicle three times a week, just as we have now, and we have plenty to say; and I remember the clacking noise there always was when some of the ladies got together. But, probably, schoolboys talk more than ladies. At last there was a terrible, sad thing happened.” Miss Matty got up, went to the door, and opened it; no one was there. She rang the bell for Martha, and when Martha came, her mistress told her to go for eggs to a farm at the other end of the town. “I will lock the door after you, Martha. You are not afraid to go, are you?” “No, ma’am, not at all; Jem Hearn will be only too proud to go with me.” Miss Matty drew herself up, and as soon as we were alone, she wished that Martha had more maidenly reserve. “We’ll put out the candle, my dear. We can talk just as well by firelight, you know. There! Well, you see, Deborah had gone from home for a fortnight or so; it was a very still, quiet day, I remember, overhead; and the lilacs were all in flower, so I suppose it was spring. My father had gone out to see some sick people in the parish; I recollect seeing him leave the house with his wig and shovel-hat and cane. What possessed our poor Peter I don’t know; he had the sweetest temper, and yet he always seemed to like to plague Deborah. She never laughed at his jokes, and thought him ungenteel, and not careful enough about improving his mind; and that vexed him. “Well! he went to her room, it seems, and dressed himself in her old gown, and shawl, and bonnet; just the things she used to wear in Cranford, and was known by everywhere; and he made the pillow into a little—you are sure you locked the door, my dear, for I should not like anyone to hear—into—into a little baby, with white long clothes. It was only, as he told me afterwards, to make something to talk about in the town; he never thought of it as affecting Deborah. And he went and walked up and down in the Filbert walk—just half-hidden by the rails, and half-seen; and he cuddled his pillow, just like a baby, and talked to it all the nonsense people do. Oh dear! and my father came stepping stately up the street, as he always did; and what should he see but a little black crowd of people—I daresay as many as twenty—all peeping through his garden rails. So he thought, at first, they were only looking at a new rhododendron that was in full bloom, and that he was very proud of; and he walked slower, that they might have more time to admire. And he wondered if he could make out a sermon from the occasion, and thought, perhaps, there was some relation between the rhododendrons and the lilies of the field. My poor father! When he came nearer, he began to wonder that they did not see him; but their heads were all so close together, peeping and peeping! My father was amongst them, meaning, he said, to ask them to walk into the garden with him, and admire the beautiful vegetable production, when—oh, my dear, I tremble to think of it—he looked through the rails himself, and saw—I don’t know what he thought he saw, but old Clare told me his face went quite grey-white with anger, and his eyes blazed out under his frowning black brows; and he spoke out—oh, so terribly!—and bade them all stop where they were—not one of them to go, not one of them to stir a step; and, swift as light, he was in at the garden door, and down the Filbert walk, and seized hold of poor Peter, and tore his clothes off his back—bonnet, shawl, gown, and all—and threw the pillow among the people over the railings: and then he was very, very angry indeed, and before all the people he lifted up his cane and flogged Peter! “My dear, that boy’s trick, on that sunny day, when all seemed going straight and well, broke my mother’s heart, and changed my father for life. It did, indeed. Old Clare said, Peter looked as white as my father; and stood as still as a statue to be flogged; and my father struck hard! When my father stopped to take breath, Peter said, ‘Have

Translation

Translate and read this book in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this book to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Cranford Books." Literature.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2024. Web. 23 Nov. 2024. <https://www.literature.com/book/cranford_1444>.

Discuss this Cranford book with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In